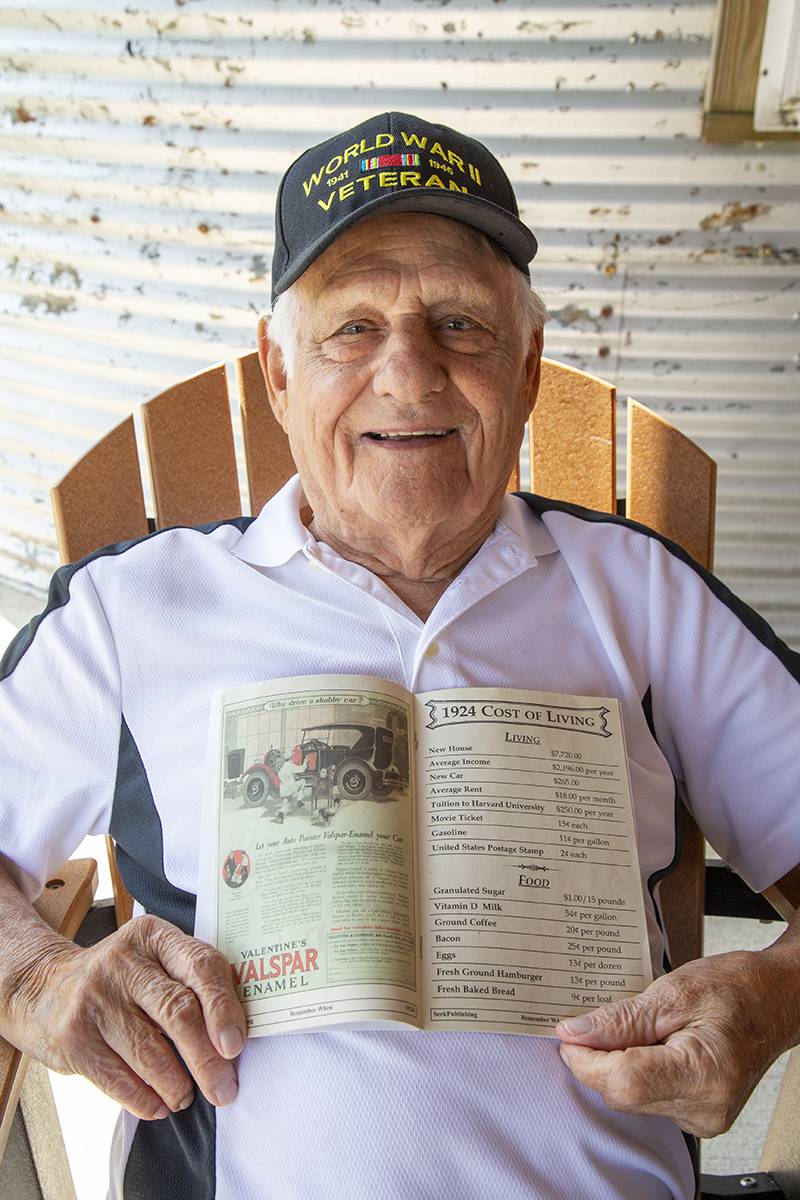

Photo by Steve Ognibene

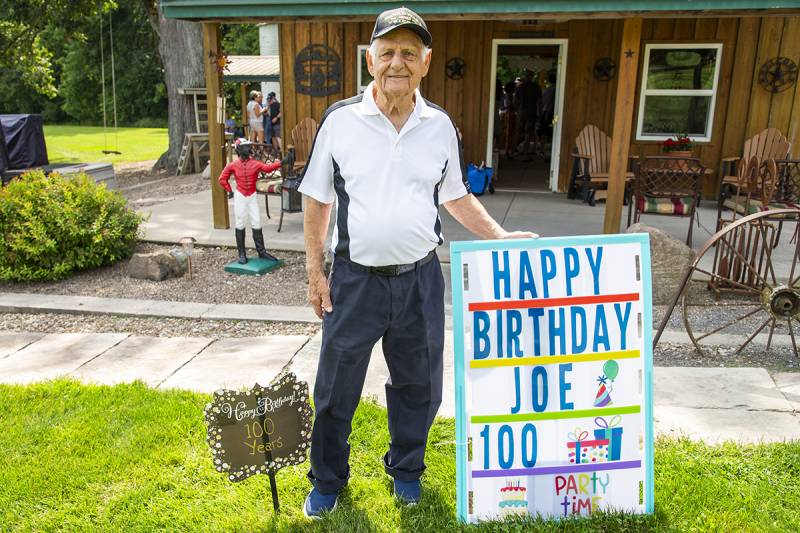

For Joseph Oddo, a Batavia native and Army veteran, it didn’t take long to name what’s kept him going for a century.

“I always help people out. That’s why I think the Lord blessed me, because, you know, the things I did in my life to help people,” the newly turned 100-year-old said during an interview with The Batavian. “I worked with people. I kept going all the time.”

Oddo will be celebrating his 75th wedding anniversary with his wife Fran on Sept. 24 — a date he joked he had not better forget. She stayed home to care for their children while he was on the road a lot, he said, as his work ethic didn’t just get him through jobs but through life.

“So everything worked out,” he said. “I kept myself busy, kept going. I always did that. When you come from a family of 10 kids …”

As the oldest in his family, he learned early on, which originated from his dad arriving “off the boat” from Sicily with a sponsorship from a Le Roy resident, that he needed to forge ahead with whatever came his way.

That included doing his patriotic duty right out of high school graduation in 1942, he said. A military draft had just been declared, and the government wasted no time pulling young boys into service. Oddo was drafted into the U.S. Army, where he served with the Signal Corps 234, a 3342 signal battalion, he said.

“I still remember, and in the battalion, various different companies. So I was a 231st company, which dealt with radio, telephone and teletype. My job was a W8, a double E day was a field telephone. That was my job, and I made sure that those are operating, and the people that had them made sure that they were getting the right information,” he said. “Because, you know, we were in Persia, they call it Iran today. See, when the Germans pushed, I mean they pushed, what’s it called, the Germans into Russia, came in with a lot of equipment, they talked about, they came along with tanks and guns and everything else.

We were just outside of Tehran into white Russia, so to speak, and that’s where we were stationed, and that’s how we kept the communications going from that point on because we could reach the troops and everybody from that point,” he said. “I served three years in World War II. I got my notice in December ’42, so in January ’43 I got inducted. I went to Fort Niagara.”

He became a leader right away when he was put in charge of troops. Then, he said, they boarded a train to New Jersey for training.

“And then all of a sudden, I had to go to Fort Monmouth for two months. And it teaches all the communications of telephone and teletype and radio and all that,” he said, referring to another time during service. “We all worked together and stuff like that. Occasionally, we had guard duty. They had a lot of German prisoners, we used to guard them at night time, that was our duty some times. We put switchboards out in the field and we had to operate switchboards because they were contacting what was on the other side of Germany.”

When he returned in January 1946, he resumed working at Doehler Jarvis even though he was “a little upset” that he couldn’t go on to school.

“When I couldn’t go to school, I had to go to the Army. I did my duty and said, ‘Why did you pick on me? I was only 18 years old, you know. But you had to serve your country. I did it,” he said. “I was told Jarvis said they wanted me; I became a steward. They made me the president of the union. I ran for president, and that was president of four plants in Chicago, Toledo, Grand Rapids and Pottstown, Pennsylvania.”

He did such a great job, in fact, that he was offered a job in Detroit for the United Auto Workers. Sell your house and move, he was told. He worked with the union for many years, negotiating contracts and such, traveling to California and “all over the place,” he said. He was so good at negotiating and so fierce that he was even dubbed “Jimmy Hoffa,” he said.

He couldn’t sell their local home and move, however, due to his wife’s mother, who had a disability and wanted her daughter close by.

Oddo never had a gap in employment, being offered various jobs throughout his life — a testament to that work ethic no doubt. He and Fran have two children, Sal Oddo and Marianne Anderson, and they still live in the Southside home they bought in 1960.

Through all these years, he has retained his memories and the drive to do what Joe Oddo does best.

“Keep going; it’s the key. Don’t stop,” he said. “I’m 100 years old, I’m still going. I do things, you know, work outside, clean. I do everything right now.”

Photo by Steve Ognibene

Photo by Steve Ognibene

Photo by Steve Ognibene