History of the Richmond Mansion and unfortunate demolition

Batavia, like many other communities, has lost many buildings that were a reminder of the city's development. The possibly most glaring example is the Richmond Mansion, likely the most magnificent home built in Batavia.

It was best known as the home of Dean and Mary Richmond, who became one of the wealthiest families in the area. Their stunning home reflected their wealth and influence and was an artifact of their importance long after they were gone.

The central part of the stately house located on East Main Street in Batavia was built in 1838, not by the Richmond Family, but by Colonel William Davis.

Davis was a dry goods merchant who served the community in many capacities until his death in 1842. Davis was a member of the committee charged with investigating the disappearance of William Morgan, who was famous for revealing the secrets of the Masonic Order. Davis was also a member of the board of the first local banking institution and assisted in defending the Holland Land Office from near attack in 1836 during the “Land Office War.”

Judge Edgar Dibble purchased the home from Davis’ widow in 1846. Dibble was a leader of the Genesee County Agricultural Society and was the first Democrat elected to a county office since the Morgan affair in 1826. Dibble made extensive modifications to the house before it was sold to Dean and his wife, Mary Richmond, in 1854.

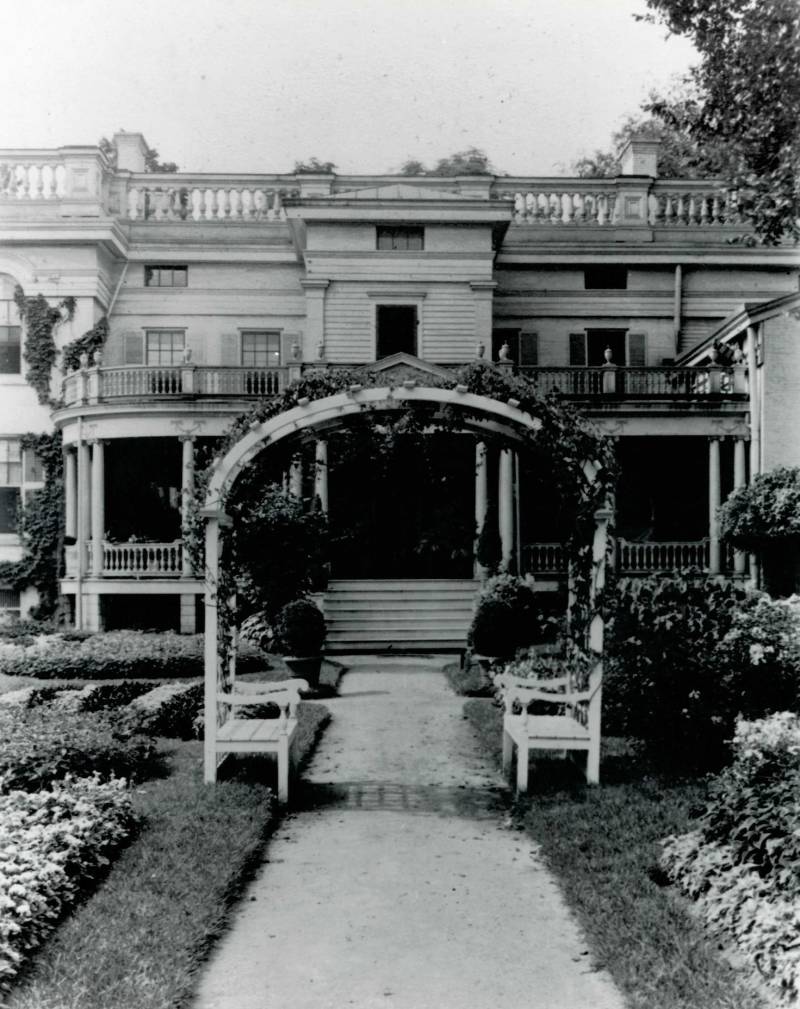

Dean Richmond was a railroad magnate, first for the Utica & Buffalo Railroad and then the New York Central. From 1864 to 1866, he was its president. Under the ownership of Dean and Mary, the home was continually renovated and enlarged. These modifications made the Greek revival style house to be the preeminent of the area.

The portico and columns, which became synonymous with the structure, were added by the Richmond, along with a building-wide balcony. Mary also created a series of beautiful gardens around the home with rare and imported plants and flowers. They were complete with a large greenhouse. A wrought iron fence, which still stands, and sunken Italian gardens fronted the structure.

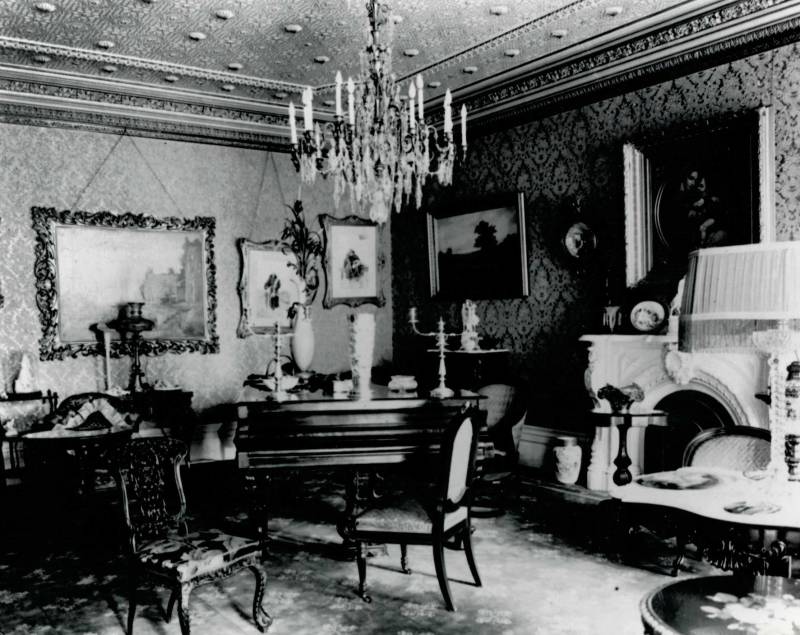

The interior matched the exterior in terms of its lavishness. The rooms were decorated with rosewood and mahogany, as well as plastered moldings and ceiling medallions. This included the dining room, which was famous for its yellow-damsked wall and yellow velvet carpets. The master bathroom had solid silver fittings with Tiffany marks. The home was so large that entire horse-drawn carriages laden with supplies would be driven right into the basement. This access was also used to deliver the enormous amount of coal needed to fuel the three furnaces.

After Dean’s death in 1866, Mary continued to live in the home until her death in 1895. It then passed to their daughter, Adelaide, who left it to her niece, Adelaide, and finally to her brother Watts, who eventually sold the mansion.

In 1928, the building was sold to the Children’s Home Association and operated as the county Children’s Home until 1967, providing a home atmosphere for countless local children.

The Batavia City School District then purchased it for $75,000. The Richmond Mansion was demolished by the school district’s Board of Education after three years of disputes with the local Landmark Society over what should be done with the building. The plot where the mansion once stood is now a parking lot located between the Richmond Memorial Library, also built by Mary Richmond and St. Joseph’s Church.

Some pieces of furniture and other fixtures have survived and are a part of the Holland Land Office Museum’s collection, including an ornate gold hallway mirror, rosewood carved bookcases, and marble fireplace mantle. Besides these pieces, the only remnant left is the stretch of the original rod iron fence that remains in front of the mansion’s original location.