Speaker at 400 Towers for Black History Month dinner outlines record of race and healthcare in America

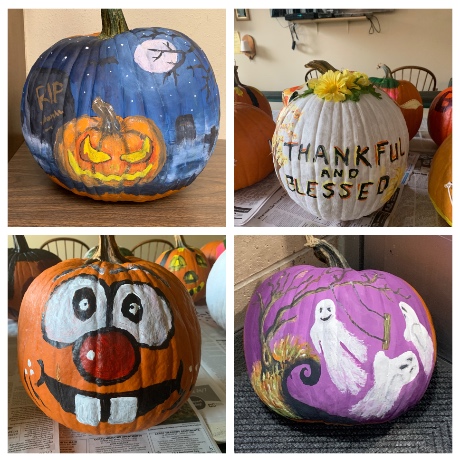

Photo by Howard Owens.

Equal treatment in medicine has been a long struggle for Black Americans, Dr. Cassandra Williams told more than two dozen 400 Towers residents on Thursday following a Black History Celebration Dinner.

Williams is the medical director for Terrace View Long Term Care in Buffalo.

"I grew up on the east side of Buffalo," Williams said. "For the people that are not from Buffalo, it’s a predominantly black neighborhood. My dad had a high school education. My mom had an associate's degree. From as early as the fifth grade, I wanted to be a doctor. That's all I knew. There were none in my community, of course, but I wanted to do that. There was so much sickness, from my brother having lymphoma and taking chemotherapy at nine to my father being a brittle type-one diabetic and my grandmother having schizophrenia. I saw doctors as one of the ones that made people better."

(Her brother was cured, she said, which brought a round of applause. He currently lives in Fairport.)

Black History Month, Williams told the residents, has been celebrated in the U.S. since 1976, when President Gerald Ford recognized it nationally as a time to celebrate the achievements of African Americans.

It grew out of Negro History Week, which was started by historian Carter G. Woodson and others in 1926. They chose the second week in February to coincide with the birthdays of President Abraham Lincoln and escaped slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

Then, Williams ran through important dates in medicine for African Americans.

- Dr. James Durham was born into slavery in 1762. He bought his freedom and began his own medical practice, becoming the first Black doctor in the United States. He is best known for saving more Yellow Fever patients than any other physician.

- In 1847, Dr. James McCune Smith graduated from the University of Glasgow, becoming the first African American to earn a medical degree.

- In 1862, in Augusta, Ga., the Jackson Street Hospital was the first hospital for African Americans. It had 50 beds.

- In 1864, Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler was the first African American female to earn a medical degree.

- In 1868, Howard University was established to educate African American doctors.

Howard University was needed, Williams said, because segregation prevented Black students from attending all-white schools.

Also, in response to racism, in 1895, the National Medical Association was founded since African Americans were barred from other established medical groups like the American Medical Association.

- In 1936, Dr. William Augustus Hinton's book on syphilis treatment was the first medical textbook written by an African American.

- In 1968, Prentice Harrison was the first African American to be formally educated as a physician assistant.

- In 1973, Patricia Bass was the first African American to complete a residency in ophthalmology. She later founded the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness.

- In 1981, Alexa Canada became the first African American woman neurosurgeon.

"Now, if you think about that, in 1981, she's the first African American woman neurosurgeon. That's not that long ago," Williams said. "That's like, that's after I was born. So that's recent."

The legacy of racism lingers. As of 2019, only 5% of the doctors in the U.S. are Black, while 13.6% of the population is Black.

She also discussed the disparities in health outcomes for African Americans compared to white Americans.

"There remains significant racial disparities, disparities in life expectancy, maternal deaths, and infant mortality amongst African Americans," Williams said. "Again, why? Why is that? What accounts for the Black-White health disparities? Is it family formation, culture, education, neighborhood disadvantage, employment insurance? None of these fully account for the difference when making all things equal, such as location, education, income level, city or rural, African Americans continue to have worse outcomes with most medical conditions."

One potential cause may be distrust of healthcare providers in African American communities because of past practices of the white establishment. That came up most recently during the pandemic, and there was a high rate of vaccine resistance in Black communities to vaccines.

"Granted, not just African Americans but people from all races were hesitant to take the vaccine for their own reasons, but the reason for a lot of African Americans was because of a history of unethical and racially targeted experiments," Williams said. "A few examples include gruesome experiments on enslaved people, such as doing surgery without anesthesia to see what would happen. Forced sterilization of black women ... and the very infamous Tuskegee experiment, where people who had syphilis, which could lead to anything from sores to brain damage, were not treated."

White doctors wanted to see what would happen to untreated Black patients, so while the patients thought they were receiving penicillin shots, they were actually getting injected with a saline solution.

"Penicillin is one of the cheapest, the oldest antibiotics you can get your hands on," she said.

"They were coming and coming weekly and getting shots, just like everybody else, but they were getting saline, right? They were getting nothing, but they wanted to see, but they were doing tests on them to see sores, the brain damage, to see what would happen."

That's part of the reason Blacks in America continue to distrust the medical establishment.

"Studies have found African Americans are consistently under-treated for pain, and often when they are evaluated by medical professionals, there are assumptions, such as, they are not married, uneducated or come from a poor environment," Williams said. "This is not in history. This is today. This is current data."

As a Black woman doctor, Williams has encountered prejudice throughout her career.

"In this day and age, there have been some subtle and some not-so-subtle racial and sexist roadblocks and remarks that I've had to deal with and persevere through," Williams said. "I've probably been asked if I was a CNA, the housekeeper, the nurse, the dietitian, more than others. Even though I wear my white coat all the time -- and that's the reason I wear it all the time, because the people I work with and work around look just like me. When I walk into the room, they don't know who I am so I introduce myself. I wear my white coat. I wear my stethoscope. Some people still say. "I didn't see the doctor today. "The doctor never came and saw me. They're like, 'Doctor? I'm sure she was in here.' They're like, "Oh, that was the doctor?' 'Yeah, that was her. That was the doctor.'"

Even so, Williams loves what she does.

"At this stage of my life, I love my career choice. I love the challenge. I'm grateful to be in the profession I'm in. I thank God, who is the head of my life, for guiding my steps through this journey."

Photo by Howard Owens.