Crista Boldt

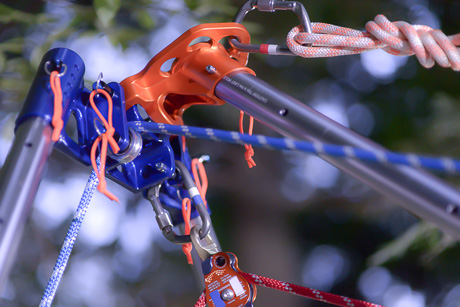

Pop quiz: You're a code enforcement officer and your job is to measure a fence to see if it is less than six feet high and therefore conforms to the local building code. Do you measure from the side of the fence of the property owner who built the fence, or do you measure from the other side?

In Stafford, Code Enforcement Officer Lester Mullen measured from the non-owner side. That was his solution to a question that apparently has no correct answer under existing town law, but has unleashed a protracted legal battle that has consumed at least $10,000 of taxpayer money and caused James Pontillo to shell out nearly $10,000 in attorneys fees.

The two adjoining properties are different grades, accounting for a variance in fence height from one side to the other.

The issue of the fence has morphed into a soap opera of sorts and still has no resolution; though, it was hashed out at great length at a public hearing before the zoning board of appeals on Monday night.

Peter J. Sorgi, the attorney for Pontillo, explained it this way: His client decided to build a fence two years ago between his property, the ancient and former Odd Fellows Hall on Stafford's historic four corners at Main Road and Morganville Road, and the property to the west, where Tom Englerth erected a steel-roofed building that is currently leased by the Stafford Trading Post and a hair salon.

The feud between Pontillo and Englerth is well documented. It's genesis seems to be Pontillo's successful bid to buy the property at 6177 Main Road in 2010 for $40,700. His purchase of the building was applauded by members of the Stafford Historical Society and Pontillo promised to clean it up, restore it and return it to a useful commercial and residential property. There was concern at the time that Englerth wanted to move or raze the building and open a gas station at the location.

Over the years, there have been numerous police calls to the location as Pontillo and Englerth have scrapped over access to Englerth's property for high lifts for roof workers, snow removal, garbage dumping and property lines.

The fence issue wound up in court, and a Stafford judge ordered the fence removed. On appeal, Robert C. Noonan, in his capacity as Superior Court judge, upheld the ruling that the fence was out of compliance with local ordinance -- supporting Mullen's measurements -- but reversed the lower court's order that the fence be removed.

Pontillo was ordered to pay a $2,500 fine, but the fence still stands and Pontillo is seeking an area variance for an eight-foot-tall fence, though he unofficially contends the fence, measured on his side of the property line, is only six feet tall.

The meeting Monday night can only be described as contentious, with Pontillo already seeming to have scored some demerits with Crista Boldt, chairwoman of the ZBA, for blaming the town at last week's County Planning Board meeting for his application lacking surveys, plans and photos. Pontillo claimed to have provided those items to the town and was surprised the town hadn't passed along those exhibits.

"I don't want untrue things getting said when you go to other boards," Boldt said. "It reflects poorly on the town."

Sorgi explained Pontillo's remarks to the county as a misunderstanding. The Town of Stafford doesn't require those exhibits, but the county board wanted to review those details. Pontillo, he said, had at one time or another provided the town with all of those materials, but not part of this specific application, because the town didn't require those items be attached to the application.

Sorgi then provided a brief history lesson on the local planning process, which only began in New York about 100 years ago.

There are court cases that outline the role of a zoning board, he said, which is to act as a safety valve to help interpret zoning ordinances. It's role in considering a variance was to balance the benefits to the property owner against the health, safety and welfare of the local community.

James Pontillo

He provided, from NYS code, the five criteria the board must consider and explained how all five criteria weigh in favor of his client.

The benefits Pontillo seeks, Sorgi said, is to hide what he described as an unsightly mess next door, from exposed dumpsters to an unkempt back lawn and junk strewn about (when we look at the property after the meeting, the lawn had been cut within the past two weeks and there were only a few loose items in the yard).

Town Attorney Kevin Earl said a six-foot fence accomplishes the same goal, but Sorgi said not if Pontillo does as planned and builds a back deck on the property, which will be used for dining and drinking.

The fence also prevents snow from being piled up against the old building and makes use of the westside fire escape safer.

The board must consider, Sorgi said, whether the change hurts the character of the neighborhood or is a detriment to nearby properties. He said the fence does no harm and with the 80-foot flower box Pontillo has installed, actually enhances the neighborhood.

The board must consider whether the applicant has a feasible alternative, and Sorgi said there is none.

The request for a variance must be substantial, according to state law, and since a court has ruled the fence is too high, the variance is necessary to achieve Pontillo's desired benefits.

The board must consider whether the variance, if granted, will adversely impact the physical or environmental conditions of the neighborhood.

The answer, Sorgi, said is no.

Finally, the board must consider whether the need for the variance is the result of an issue self-created by the applicant. It wasn't, Sorgi said, because the town doesn't require any sort of permit for a six-foot-high fence and since his client thought, by his own measurements, he was building a six-foot-high fence, there was no official method to confirm with the town that the fence was within the required height. The town didn't object to the fence, Sorgi said, until it was nearly completed.

The only speakers at the public hearing, five altogether and all local residents, each supported Pontillo's variance request.

During the course of the presentation, there were tense moments.

Sorgi took issue with Mullen declining to speak on the record, in front of the press and public, about his position on the variance request. Mullen specifically cited the presence of news media as his reason for not speaking.

When Sorgi left out "physical" to go with "environmental" on the criteria for the board to consider, Boldt called him on it.

Sorgi raised the issue of a fence on the other side of Englerth's property, built by Englerth, that exceeds the six-foot height limit, but Englerth is apparently not facing the same level of scrutiny over that fence, Sorgi said, as his client.

Pontillo accused Englerth of trying to fudge the property line before his fence was built by moving a surveyor's stake at the back of the property by as much as six feet. That dispute led to an accusation of trespassing by Englerth and one of the multiple visits by troopers to mitigate tensions over the past couple of years.

Sorgi tossed a couple of barbs Attorney Earl's way, expressing disdain that Earl threatened to have Pontillo arrested if he didn't take the fence down. Earl argued that isn't exactly what he said, that he merely mentioned that a consequence of failure to abide by zoning law could result in a jail sentence, which he has sought before in other jurisdictions, where he has also served as a municipal attorney, for similar violations. It's not an abnormal response to zoning violations by municipal attorneys.

Sorgi also peppered Earl, whom he accused of chasing billable hours, with questions about why he was even at the meeting: Was he there as a private citizen or as the town's attorney? Earl said Town Supervisor Robert Clement asked him to be there, and Sorgi said that Clement, under state law, didn't have the authority to ask Earl to represent the town board at the meeting, that it took a vote of the board for such an action.

As a result of the meeting, both attorneys are now on record on two key points:

- Earl said "nobody is trying to get the fence taken down." The town officially has no position on how the ZBA should vote on the variance request.

- Sorgi said his client is willing to stipulate for the sake of the variance application that the fence is eight feet tall.

In the midst of this rancor, Sorgi reminded the ZBA that its job was to weigh the evidence without consideration for personalities or past history.

"This isn't about James Pontillo or whether you like him or whether you like this neighbor more than that neighbor," Sorgi said. "This is about whether the request benefits the applicant without doing harm to the health, safety and welfare of the community. That's it. Whether you like somebody isn't the question. It's a simple test."

The ZBA is scheduled to vote on the application for a variance at its September meeting.

Previously:

Attorney Peter Sorgi