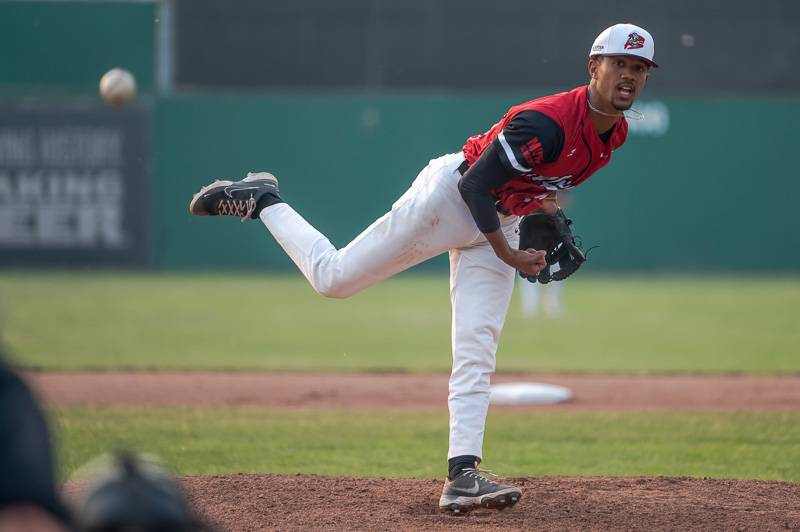

Photo by Howard Owens.

The leaders of Minor League Baseball, and, by extension, Major League Baseball, didn't think Batavia could support a professional baseball team, and those Lords of the game looked for years for an opportunity to relocate the New York-Penn League's founding member to another city.

That search for new ownership and a new venue lasted until MLB just got tired of the entire MiLB structure and shut down the historic NYPL.

"The players aren't as gifted, but you could make the argument that games are a lot more fun to watch."

Bardenwerper’s book on baseball, which will feature the Batavia Muckdogs, is about 3/4 finished and he expects it to be on store shelves in the fall of 2024.

Submitted photo.

MLB and MiLB leaders blamed the fans of Batavia, the region, and Dwyer Stadium itself for the lack of fan interest in the teams they were putting on the field.

After all, they were bringing "prospects" to Batavia; young men with at least some slim chance of getting in a few major league innings before they moved on to other careers. And once in a while, if you came to Dwyer Stadium often enough, you might get to see a future star pass through. That should be enough, was the seeming assumption of baseball executives.

Turns out, maybe the problem wasn't the fans after all. Nor the facility. Maybe the problem was that assumption.

Maybe the men and women brought in to run the team, the leaders of the leagues, and the management of the MLB affiliates, which included, in recent years, the Cardinals and the Marlins, just didn't do the right things to generate fan interest in the game.

After head groundskeeper Cooper Thomson turned the turf of Dwyer Stadium into an All-Star Game-worthy surface, it still wasn't enough to keep the team in Batavia, and fans seemed to know it. They continued to only attend home games sporadically. A night of 1,000 people in the stands was a good night. It usually took Friday night fireworks to pack in more than 1,500 people.

On Tuesday night, 2,877 baseball fans held tickets for a Perfect Game Collegiate Baseball League between two teams with rosters filled with young players who are far less likely, on average, to ever play a professional game, let alone reach the major leagues.

On Sunday, attendance was 2,808.

For the home opener on Saturday, attendance was perhaps a record for organized baseball in Batavia: 3,711.

Perhaps Rob Manfred, the commissioner of Major League Baseball, who oversaw the destruction of the minor league system, should talk without Robbie and Nellie Nichols, the current owners of the Muckdogs, about how to promote baseball in a small town.

The main difference between the affiliated Muckdogs and the collegiate Muckdogs, William Bardenwerper told The Batavian before Tuesday's game, is the collegiate players are fan-friendly. They're out in the community. They talk with fans at games. They're friendly with the kids, always.

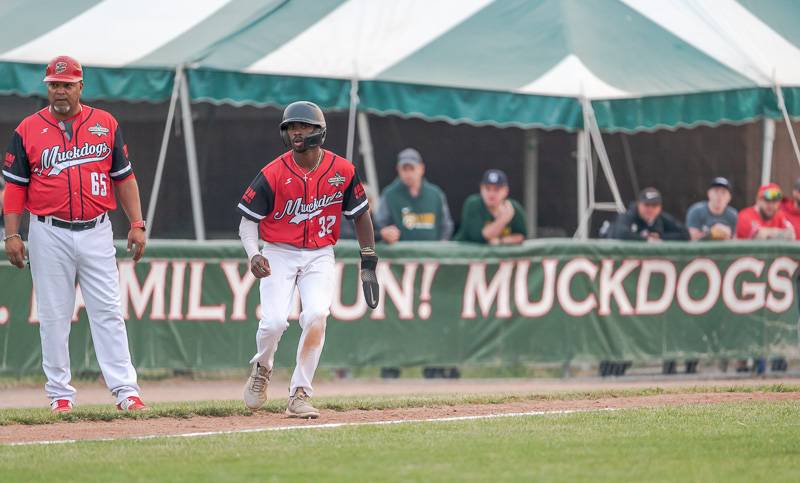

And that's by design. From the day he arrived in Batavia in 2021, Robbie Nichols has talked about wanting players on his team who are willing to make themselves part of the community for the two summer months they're in Batavia.

Manager Joey Martinez wants to recruit the best baseball talent he can, and he thinks he and his staff have built a special and talented team for 2023, but he told The Batavian in a pre-season interview that character is also part of the recruiting evaluation.

"We try to just get guys that are going to come into this community and be a part of it," Martinez said. "(We want them to) represent the Muckdogs name everywhere and every day."

Bardenwerper said that community commitment is obvious and it's paying dividends.

"Robbie and Nellie, the owners, as well as Joey Martinez, as manager, have fostered a community spirit," Bardenwerper said. "It's part of their responsibility in the summer to do everything they can to be there for the community, to support the community.”

Bardenwerper is a non-fiction writer who is working on a book that will look at the demise of the New York Penn-League through the lens of the Batavia Muckdogs.

He spent a good deal of time in Batavia last season, attending games, interviewing fans, and getting to know the community and its love of baseball. He wasn't around in the affiliated-Muckdogs days, but he's seen the community embrace the collegiate Muckdogs.

He said professional minor league players tend to be more distant. They quickly grow accustomed to playing before larger crowds, so they're less engaged with the fans.

"These players (the current Muckdogs) love interacting with the fans," Bardenwerper said. "They're often from smaller schools where they might get 100 people in the stands. Now they're playing in front of thousands of people.”

There's no doubt, Bardenwerper said, the quality of play isn't the same. There are fewer pitchers throwing 95 mph, fewer home runs, and more errors, but collegiate baseball at this level has its advantages for baseball fans, as well, the writer noted.

"Joe Maddon (former major league manager) wrote that 35 percent of the at-bats in major league games these days, you do not need anybody on the field except a pitcher, a catcher and a batter (because 35 percent of at-bats now end in a strikeout or a home run), and until this year, because of the pitch clock, baseball became slow," Bardenwerper said. "This baseball, the kind you see at these games, is like a throwback to what you used to see at games. You see steals. You see hit-and-runs. You see more extra-base hits.

Joey Martinez is an aggressive manager. There's more action on the basepaths. There's nobody with statistics, a spreadsheet, and a computer telling the manager every decision he should make. This is more like going back and watching a baseball game in the 1980s. The players aren't as gifted, but you could make the argument that games are a lot more fun to watch."

If not for the pandemic, Bardenwerper wouldn't be writing about the Muckdogs. In 2019, he pitched his publisher on writing a book about the Appalachian League. He was going to visit all those small towns in 2020, get to know them and their teams, and chronicle small-town baseball through that lens. But the 2020 season got canceled by COVID, and by 2021, neither the Appalachian League nor the New York-Penn League existed.

Eliminating those leagues, at least according to the explanations given by MLB leaders, Bardenwerper said, made little sense. The excuse given was MLB wanted to protect their precious and expensive talent from 12-hour bus trips and substandard stadiums. While those might be valid complaints in leagues out west, it wasn't true of leagues in the Northeast. For the most part, even in the NYPL, which had expanded its boundaries in recent years, teams were within a few hours of each other, and with a couple of exceptions in the Appalachian League, playing conditions were good.

"The reasons offered for contraction were disingenuous and not consistent with the teams that were contracted," Bardenwerper said.

But what has become MLB's loss has become Batavia's gain, especially for young fans who are made more a part of the atmosphere at Dwyer Stadium. Kids can get autographs, baseballs, and batting gloves from players at any time, even while there's action on the field. Young fans are never told not to bother players in the dugouts and bullpens. The players never act like they don't hear the kids, turn a cold shoulder and walk away.

And that's an important part of the connection with the community, Bardenwerper said.

"The kids don't know the difference between these college kids and the next Bryce Harper," Bardenwerper said. "They just see these guys in cool uniforms signing autographs."

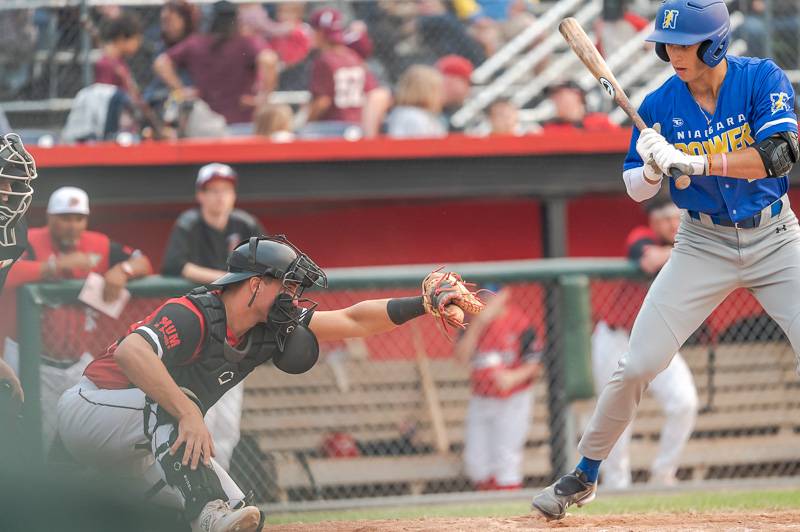

Given the fan-friendly atmosphere at Dwyer these days, it's doubtful many fans walked away from Tuesday's game dissatisfied, even though the home team fell to 2-2 on the young season with a loss to Niagara Power, 3-1.

Photos by Howard Owens. For more photos and to purchase prints, click here.

Photo by Howard Owens.

Photo by Howard Owens.

Photos by Howard Owens

Photo by Howard Owens.

Photo by Howard Owens

Photo by Howard Owens