In the half century since Gary Maha started his law enforcement career, a lot has changed about being a cop.

There's the obvious changes -- digital communication, cameras, phones, computers. Then there are the changes of the mind, how society sees itself in the mirror and the role of the police officer in that looking-glass world.

Maha will miss some things about being in law enforcement, but he won't miss the stress.

"I just want to relax for a while," Maha said. "No more two or three o’clock in the mornings when the phone rings. You know it's not somebody checking to see how well you’re sleeping. It’s usually something that’s bad or something’s happened you need to respond to. I won't miss that kind of stuff, all the sleepless nights. I mean, I don’t sleep well at all at night because you’re always concerned and worried either one of your people are going to get hurt or something’s going to happen. You wait for the phone call."

Maha was handed his first straw Stetson, a badge and a .38-caliber revolver in 1967.

In 1967, Genesee County was still pretty much the world Gary Maha grew up in.

A child of Corfu, Maha remembers a village that was a chummy, tight-knit group. People left their keys in their cars, didn't lock their doors and the kids went to the local market or local diner for something to eat and just hang out. Or they played sports. There were no drugs. There were few children raised in single-parent homes or by grandparents. There was one deputy who patrolled the entire county during the night shift.

"Back in those days, you knew your neighbors," Maha said. "You know almost everybody who lived in the Village of Corfu at the time. That’s not the case nowadays with the transient population; people don’t know their neighbors like they used to."

Maha was the son of the man who ran the village court, the local justice of the peace. That's where he developed an interest in law enforcement. Discipline and integrity were traits Maha said he got from his parents.

"My mother was a stay-at-home mom and my father owned a greenhouse in Corfu and she worked a lot in the greenhouse but they were both home all the time," Maha said. "They weren’t strict parents, you know, but you got to follow the rules."

In high school -- it was Corfu High School, then -- there was more discipline and a touch of leadership experience. He played basketball and baseball and became the football team's starting quarterback.

In the early 1960s, the United States was just starting to get involved in Vietnam and Maha joined the Army. He served three years, including a 13-month tour in Korea, then returned home for college and an eventual job in the dispatch center of the New York State Police in Batavia.

It was, in that job, a year when Genesee County's undersheriff walked into the darkroom where Maha was developing photos for a trooper and suggested he apply for a job as a deputy.

A few weeks of training, a week of on-the-job training, and Maha became that lone patrolman prowling the county's back roads.

"I remember once going from Darien to Bergen to respond to an accident," Maha said. "By the time I got there, the guy’s still lying in the middle of the road."

Those were different times, but Maha was always steadfast in his integrity. When we talked about some of the things that have tripped up Sheriff's in other jurisdictions over the years, he recalled those who skimmed money or had sexual affairs and these transgressions cost them their jobs.

"I remember stopping a girl, and she’s out to do anything, anything to get out of the ticket mess and I said, 'I’m sorry. Here you are,' ” and Maha motions handing her a ticket.

Maha said he warns deputies they will face these temptations.

"That’s one thing I tell officers, too, you know," Maha said. "Don’t fall in the death trap because once that happens, they've got your career right there in their hands. They’re going to play that trump card when it’s good for them, not for you. I’m sure to tell all these guys -- because I did when I was a young deputy -- you will get propositioned."

Maha's reputation for integrity extends beyond the border of Genesee County. Rare among those in local law enforcement, he has a top secret clearance from the FBI. Every year, he teaches an ethics seminar through the New York Sheriffs' Association for new sheriffs. He tells them all the same thing, "you have to take care of things at home."

He's seen a sheriff become more enamored with his cottage at the lake than what was going on in his own county. He's also seen sheriffs who think they're on top of the world and can't be touched.

"They have a big ego and that comes back to haunt them and they lose elections," Maha said. "It's the same with a lot of people. They get involved with women or alcohol or greed sometimes. I remember a sheriff many years ago who was a good sheriff, well liked, but he had a drug seizure fund and he was using that to finance some of his personal expenses. He got caught, got charged and spent time in the federal prison -- stupid stuff."

Other sheriffs lose elections. Not Gary Maha. He ran every four years from 1988 to 2012 unopposed.

The route toward sheriff for Gary Maha may have started when his boss in 1972, Sheriff Frank L. Gavel, nominated him for a spot at the FBI Training Academy in Quantico, Va. Maha was accepted in his first year of eligibility. After five years in law enforcement, and at 28 years old, he was the youngest attendee.

"It's all the same courses that the FBI agents go through," Maha said. "You go through a lot of leadership courses, a lot of management courses including some operational type of courses, and it was three months away from home but it was well worth it."

By the time Maha arrived in Quantico, he was already an investigator handling some big cases.

The most memorable cases, of course, where the murder cases.

"I remember my first homicide case," Maha said. "It was over on Hundredmark Road. There was a fire in one of the shacks over there. We’re blocking off the road and a fireman found a skeleton, you know, a burned up, charred body inside.

"We had nothing to go on," Maha said. "We don’t know if it was male or female, and the way we finally identified it was female is she had an ankle bracelet on and there was a female missing out of Albion who had that type of ankle bracelet and that’s how we ended up first identifying her, and there was this guy from Oakfield. I won't mention (his name) because he did 25 years to life and he’s out. He picked her up and took her over there and he sexually abused her."

There were no witnesses and scant physical evidence, but Maha and the other investigators were able to piece things together, draw in statements the suspect made to a fellow inmate, and make a case and get a conviction.

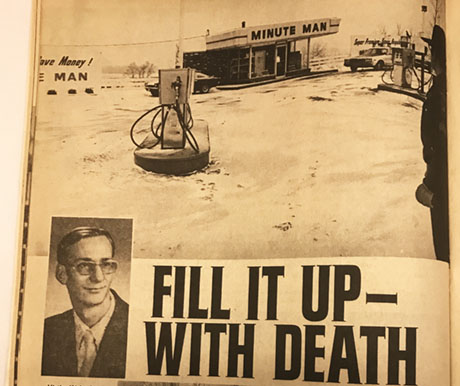

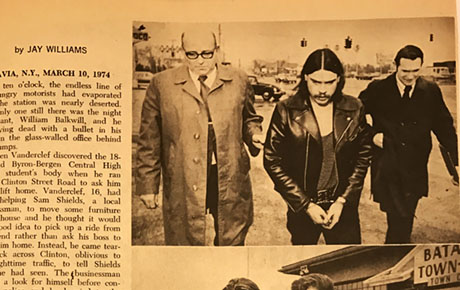

The young investigator helped secure another conviction on a murder case that became a story in "Inside Detective," the once popular pulp magazine. In that case, two young men stopped at a gas station on Clinton Street Road, where an ice cream shop is now, and one of the men went inside to rob the attendant and the other drove down the street and then came back to pick up the robber.

The driver apparently had no idea his partner shot and killed the recent high school graduate from Bergen who was working that night.

"That was another tough case," Maha said. "The main perpetrator, the actual shooter, he was on parole and he was the coldest-blooded guy I ever met in my life. I mean, he shot this young kid, 18 years old, and he shot him on the back of the head and for robbery. I don’t think he got much money and (the victim) was a great kid, too. I knew his mother. That was just a senseless shooting. It was just cold-blooded."

The shooter was an immigrant from Poland and he was deported after serving his prison sentence. Maha doesn't believe his accomplice, who lived in Brockport, returned to the area after prison.

In 1977, Maha was promoted again, this time to chief deputy.

Today, the department has a chief deputy in charge of road patrol and another in charge of investigations, but in 1977, Maha was it. He supervised both divisions.

With the bearing and demeanor of the late actor Jack Palance, Maha is usually a man of few words who can be hard to get to know. Friends say he has a wicked sense of humor and at department gatherings, he clearly enjoys a good joke. After a community event a few years ago, his wife, Sue Maha, told a local photographer that he accomplished a rare feat -- capturing the stern-faced sheriff wearing a smile in public.

The Mahas obviously enjoy each other's company, even after nearly four decades of marriage and raising two children together. They are both members of Kiwanis and at just about any social event where one goes, they're both there.

For Gary, lasting romance came a bit late in life. He had already been with the Sheriff's Office for more than a decade when he met Sue.

He met her, of course, on the job. No, he didn't pull her over with the notion of giving her a ticket. Nor was the chief deputy fraternizing with the staff.

Sue traveled the region selling photo ID systems to law enforcement agencies and it was Maha's job to review the systems for the criminal division and make a recommendation for purchase.

"That’s when I met her and we fell in love and here it is 36 years later," Maha said.

A man of few words.

Maha never set out to be sheriff. He never sought the job, he said. He didn't even think he was the one who would get it when Doug Call stepped down from the position in 1988 and recommended Maha for the governor's appointment. The governor was Mario Cuomo, a Democrat, as was Call, and Maha is a Republican. He figured the job would go to another Democrat, but Call's recommendation persuaded Cuomo that Maha was the right choice.

While other departments have had their scandals and tragic line-of-duty incidents, Maha's Sheriff's Office has largely run smoothly over the course of his career.

He credits his command staff and the folks they supervise.

He may not be out in the field every day, but good communication combined with the knowledge he gained coming up through the ranks Maha said enables him to keep pretty good tabs on his deputies.

"Some of the guys probably don't realize it, because I'm up here and they are down there, but I know what's going down there," Maha said. "I get a feel for what's going on out there in the community. I hear what's on dispatch all the time and know what's going on. I stay in contact with my chief of road patrol every day. He stops in every day and we discuss things, what's going on. I've got a good bunch of people here. They are well trained, well equipped and well educated."

Becoming a deputy is a lot harder than it was in 1967.

Where it only took Maha a few weeks of training, and no civil service exam, before he was on patrol by himself, the process for a deputy just starting out today is about a year long.

New hires who want to make it to road patrol go through an extensive background check, hours of psychological evaluation, a polygraph, physical fitness and agility tests, and a medical checkup before they're even given a chance at training. And then they're sent to a law enforcement academy for six months before three months of on-the-job training.

It's a daunting process and a lot of men and women who try don't make it.

That's one reason Maha likes hiring military veterans when he can. They have a proven track record of self-discipline and they understand the command structure.

"It's very important you choose the right person," Maha said. "We are accredited. We are the only local law enforcement agency that is accredited. We have certain standards that you have to comply with and meet. Therefore, a selection of a deputy is very important. So even though we have civil service rules and regulations to comply with, you sometimes have to pick the best of the worst. You would like to get a better officer and mostly we do, but there have been a few who washed out."

For all his sleepless nights worrying about his deputies, there has been only one line-of-duty death during Maha's tenure. That was when Frank Bordonaro passed away in his sleep following back-to-back nights of stressful calls -- a house fire in Le Roy and an ugly, fatal accident in Byron.

"That was tough on the department because Frank was a well-liked guy," Maha said. "He was great at his job, a super guy, very friendly, outgoing, and it was a shock to all of us when that happened. It hit the department hard."

It's also hit Maha hard when he's had to fire people under his command. It's not always an easy thing to do, he said. Most recently, he had to terminate a corrections officer for allegedly engaging in sexual acts with a female inmate. That was tough.

"You know, he has a small child, he's married, so that was difficult," Maha said. "I liked the guy. Some of these guys, you know, they're not deserving (of the job), you know, 'you're out of here,' but he's a decent guy and I hated to have to discipline him and let him go, but you have to."

Maintaining order and discipline is a bit of swimming against the tide of the times, which is another reason Maha has continued to emphasize integrity in deciding who gets hired and who stays.

One of the biggest changes Maha has seen over the course of his career is the decline in respect for law enforcement.

"Things have changed as far as crime goes," Maha said. "You know, drugs made a big change, gangs, you know, and I think respect not for just law enforcement but for authority, teachers, or whatever. It’s not just there anymore. There are a lot of broken homes where children are raised by one of their grandparents or no adults. It’s totally different."

So it's not totally a bad time to step aside for a guy who started out as a cop when people could still leave the keys in a car's ignition. He knows that.

That doesn't mean Maha thinks the job is impossible or can't be rewarding for the young ones coming up through the ranks. He tells them, "just do the right thing."

"Don't take any shortcuts," he said. "Make sure you follow the law and be honest. Keep your honor and just be held to a higher standard."

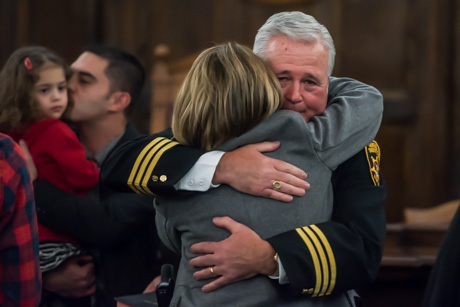

Gary Maha, second from left, being welcomed to the force with three other new deputies by Sheriff Frank L. Gavel.

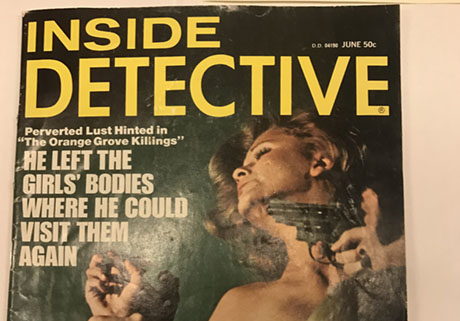

The cover of the "Inside Detective" issue that included a story about a murder in Batavia that was investigated by Gary Maha.

The first page of the story about the murder at the Minute Man gas station on Clinton Street Road, Batavia.

Gary Maha, far right, in a photo in "Inside Detective," with another investigator and a suspect in the murder.