At the intersection of Main and Ellicott stands a monument to Gen. Emory Upton, Batavia's most revered military figure, and for good reason, says history professor and now Upton biographer David J. Fitzpatrick.

Upton distinguished himself during the Civil War in battles at Salem Church, Spotsylvania, Opequon Creek, and in other engagements.

"He was one of the outstanding regimental commanders of the war," said Fitzpatrick, who teaches at Washtenaw Community College in Ann Arbor, Mich. "He had a tremendous tactical success at Spotsylvania."

The fact that Upton is still discussed among military leaders and those interested in military history, though, has more to do with his ideas and what he scribbled on paper than what he accomplished on the battlefield.

Some of what Upton wrote has led to more than 50 years of the Army officer being misunderstood and misrepresented, though, according to Fitzpatrick.

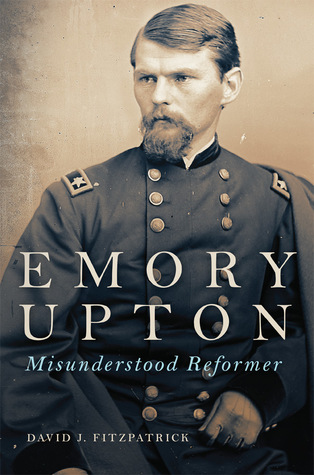

In the mid-20th century, Upton gained a reputation as a Prussian-inspired militarist with little respect for democracy. That assertion doesn't fit the documents in the historical record, Fitzpatrick contends and he makes that case in his new book: "Emory Upton: Misunderstood Reformer" (University of Oklahoma Press).

"Upton is an important figure in U.S. military history," Fitzpatrick said. "He's a figure a lot of people don't know about."

While you might expect a book steeped in military policy and battlefield strategy to be dull and dry, Fitzpatrick has written a story that is fascinating and at times even a real page-turner. Upton was a man both of action and ideas dealing with some of the most important considerations that would shape history after his death in 1881.

Batavia's Civil War hero was born to a farming family in Genesee County Aug. 27, 1839. A devout Methodist and a fervent abolitionist, Upton attended the era's most famous integrated college, Oberlin, before being accepted into West Point, graduating eighth in his class in May 1861 (The only blemish on his West Point career was a fight with a Southern cadet who made remarks behind his back, hinting that Upton had sexual relations with a black girl at Oberlin. Upton took offense and when the cadet wouldn't explain himself, Upton challenged him to a duel that became a fight in a West Point dorm.)

After the war, Upton was sent on an 18-month tour of Europe and Asia to study the military tactics of countries on those continents, especially Germany. When he returned he wrote "The Armies of Europe and Asia," "A New System of Infantry Tactics" and "Tactics for Non-Military Bodies" (aimed at civilian associations, police and fire departments); and more than 20 years after his death, his unfinished work, and most important book, "The Military Policy of the United States," was released by the War Department.

There were aspects of the military position in Germany that Upton admired and these served as a basis of Upton's recommended reforms to the U.S. military. This led to charges among critics that Upton and his like-minded reformers were trying to foist Prussian militarism on the United States.

These charges were amplified with the publication of a book in 1960 by Russell Weigley, "The American Way of War," which traced the intellectual development of military strategy and policy, and Stephen Ambrose, with "Upton and the Army," in 1964.

To Fitzpatrick, the real offense to Upton's legacy was the book by Ambrose. Weigley can be forgiven for getting Upton wrong, Fitzpatrick said, because he wasn't writing a biography, but Ambrose's biography began as his dissertation (and was published verbatim in book form).

"Ambrose was doing a biography but didn't dive into the sources he should have," Fitzpatrick said. "I think Ambrose read Weigley and just decided to echo Weigley."

Fitzpatrick poured through the letters of Upton, among other documents, with help from Sue Conklin, who at that time was Genesee County's historian, and the Holland Land Office Museum (Fitzpatrick was provided a CD of images of all the Upton letters in the HLOM's collection).

And going through Upton's letters isn't an easy task.

When arranging a visit to the County's history department, Fitzpatrick told Conklin his topic and Conklin told him, "Have you seen his handwriting?"

"No," Fitzpatrick admitted.

"You might want to consider another topic," was her droll response.

Fitzpatrick doggedly stuck with Upton's letters, however, which provided insight overlooked by Ambrose into Upton's thinking on military planning and civilian government.

Upton believed the Union could have ended the Civil War before the close of 1862 (it wouldn't end until 1865) if the military had been led by more competent officers, had been better equipped, staffed with more men, and Gen. George McClellan hadn't been hampered by interference from civilian bureaucrats, notably Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

Even though Upton had been critical of McClellan during the war, his animosity toward Stanton was even deeper.

"He starts to twist history to make Stanton into the bad guy and McClellan a genius," Fitzpatrick said. "He wrote (in a letter) that he was having a hard time with 'the McClellan question,' as he calls it. It is really causing me trouble, he said. I hear him saying that he's having a hard time making the facts fit the story. Stanton was a meddling failure, not that it was McClellan himself who caused his failures."

The focus on Stanton, however, Fitzpatrick concludes, isn't because Upton is against civilian leadership of the military, but rather a concern that a war secretary with too much power could potentially use that position subvert the country's republican form of government.

Upton's reform ideas included mandatory retirement at age 62 for officers, rotation of officers between artillery and infantry, promotion on merit rather than seniority, and more training for officers.

While Upton was distrustful of democracy -- like Alexander Hamilton, fearing mob rule -- he saw the role of the military as protecting the nation's republican style of government.

He took note of the dictatorial powers assumed by George Washington and Abraham Lincoln -- "arbitrary arrests, summary executions without trial, forced impressment of provisions, and other dangerous precedents" for Washington; and in Lincoln's case, the suspension of habeas corpus, arbitrary arrests, and the seizure of the railroads, along with "opening the treasury to irresponsible citizens" -- and concluded with a query. If that is what happens when good men without a genuine dictatorial impulse are president, what would happen if a true authoritarian took office and there was a war?

Upton wrote, "Let us not stultify ourselves by talking of the danger of an army, but rather reflect that the lack of one may at any time, in the space of two years, bring upon us even graver disasters than Long Island or Brandywine, or the two Bull Runs ... Our danger lies not in having a regular army but in the want of one."

In other words, Upton concluded a professional military, vowed to protect and defend the Constitution, as a safeguard against civilians, especially the president, grabbing dictatorial power.

Upton was one of several reformers, Fitzpatrick said, who saw the need for a more highly trained military and professional officer corps heading into the 20th century but in Upton's lifetime, most of Upton's reforms were thwarted by politics. For the North, another insurrection seemed impossible and there was no apparent external threat to U.S. sovereignty, so reform didn't seem like a pressing need. The South was distrustful of the Army in general following Reconstruction.

The lack of external threats prior to 1860 is also one reason Fitzpatrick thinks Upton's idea that the war could have lasted less than two years with better preparation is unrealistic.

While it's interesting to contemplate how history might be different if the Civil War had come to an end before 1863 -- no Jim Crow South, as one potential outcome -- it would have required the Union to have in place a large, well-trained and equipped Army by 1860 and Congress would never have approved the expenditure.

"The only reason to have a large, well-trained Army prior to 1860 was to repress the South and Congress would never have done it, so it's kind of a moot question," Fitzpatrick said. "You never could have ended the war in 1862 because you would never have gotten the Army you needed."

By 1881, Upton began suffering from debilitating headaches. He was transferred to the Presidio in San Francisco but managed to delay assuming the command for three months while he sought treatment in New York. A doctor diagnosed a sinus problem and provided an electric treatment, which brought no relief. Upton probably suffered from a brain tumor. He transferred to San Francisco but the headaches grew worse. On March 15, 1881, he wrote his last words. A two-sentence letter to the adjutant general to tender his resignation. He then apparently took his own life with a revolver.

He was proceeded in death by his wife, Emily, and they are buried together in Auburn.

At the time of his death, "Military Policy of the United States" was incomplete and unpublished. The manuscript passed to a friend and slowly it circulated among the Army's officers, gaining a reputation for its insightful look at military policy and strategy. In 1904, the War Department published the book minus three chapters.

One of the chapters dealt with Roman military history and when Fitzpatrick first came across it, he thought it rather odd. It was placed between two unrelated chapters, which was also odd.

Years later while continuing his research, Fitzpatrick recognized Upton probably wrote the chapter quickly in a period of inspiration and that it contained a lesson relevant the political situation of the time.

While Upton admired President Ulysses S. Grant as a general, he was appalled by the corruption in his administration.

The Roman Republic possesses an interest, civil as well as military. "Forewarned is forearmed." Free people like the Romans admire heroism and love to reward military achievement.

No monarch in Europe has to day [sic] the power of an American President. With the consent of the Senate, from the Chief Justice down, he has the gift of more than 90,000 civil offices, any one of which save the judiciary, he can vacate and fill at pleasure.

Ever since the acceptance of the pernicious maxim "To the victor belong the spoils," these offices, like so much gold have been distributed by the senators and representatives to the men who have been, or maybe, most loyal to themselves or the party.

With the people thus accustomed to executive corruption let us imagine, as under the Roman System, our President, in uniform, booted and spurred, galloping from the White House to the camp, his military retinue swelled by senators and representatives, fawning for favor and scrambling for spoils, how long it be asked would our liberties survive ...

To historian, from example of Rome, might not fix the exact duration of the Republic, but he could make at least one prophesy of speedy fullfllment: At the first [meeting] held at headquarters the means would be discussed of prolonging the term of the President, if not the more startling propositon to declare him President for life.

"Upton wasn't writing about Rome," Fitzpatrick said. "It was about Ulysses Grant. He was writing at a time when Grant, running for a third term in 1880, was being seriously discussed. He had come to a different opinion of Grant. He had seen all the scandals of Grant's administration, and while he admired Grant as a general, the scandals appalled him.

"He's not talking about an imaginary president climbing on a horse. He's talking about Grant. If Upton was really a militarist interested in a military government, that wouldn't have bothered him at all."