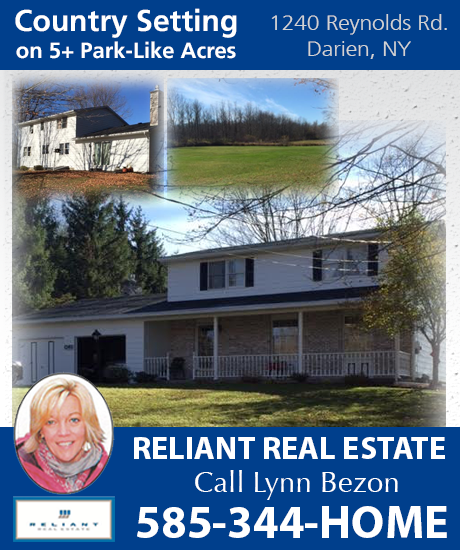

Ryan C. Bergman

Photo courtesy the Bergmans

Just before Thanksgiving, 2013, a month before his death, 26-year-old Ryan C. Bergman sat at the dining room table after an evening dinner with his parents in their home on Fargo Road, Darien, and talked with his mother about his mental health.

At age 10, his fourth-grade year, all his troubles seemed to start, Ryan told his mother as they talked through his life on a chilled and snowy November evening.

That made sense, Bernadette Bergman said. She always thought there were two turning points, downhill points, really, for her son — when he was 10 and when he was 13.

Ryan spent that fourth-grade year with a Pembroke teacher whom Bernadette described as rude, cruel and largely uncaring about Ryan’s struggles.

Bright, articulate but unable to stay focused, Ryan was a misfit among his peers. He was oblivious to social norms, craved attention and found it difficult to complete his assignments in the manner expected by his teacher.

To a public school teacher with 30 other kids to manage and guide, Ryan was, perhaps, more like a distraction than a promising literary master, a potential mathematician or computer scientist.

Bernadette, herself a teacher, recalled one parent-teacher conference that didn’t go well.

She had a notebook with her from a parenting workshop with information meant to help a student like Ryan, but Ryan’s teacher dismissed the binder and its contents as useless.

“She literally, right in front of me, ripped it apart page by page,” said Bernadette, mimicking the teacher ripping page after loose-leaf page from the book.

“‘Oh, he doesn’t need that. He doesn’t need that,’” Bernadette recalled her saying.

“If you’re rude to the parent, you can imagine what she was like in the classroom,” Bernadette said.

Her husband Richard added, “We learned from other kids later that when he got kicked out of class, he would go to the class of the grade above and he would just be rolling around in the back and the teacher would ask the class a question and nobody would know the answer, no hands would go up, and Ryan would yell out the answer. He wasn’t even paying attention and he would know the answer and shout it out.”

The first inkling the Bergmans got that Ryan might be struggling to find his place in the world came after a day out sledding with neighbors who had children right around Ryan’s age.

Ryan was a bit disruptive and the other mother told Bernadette that Ryan was “a little wild.” Bernadette was unfazed. He was just a squirrelly kid.

Later, at a pool party with the same family, Ryan found ways to irritate both children and adults. He would annoy, pester and bother, ignoring the social signals other children might decipher and realize their behavior went a little too far.

“Ryan would just do aggravating things to get people’s attention,” Richard said. “Like, he might poke you under water. He wasn’t nasty, maybe borderline nasty, just to get their attention, with it never clicking in his brain that maybe they were going to want you around less.”

Ryan was trapped in a world where his verbal skills allowed him to converse knowingly with adults, but as a matter of age and experience, his time was properly spent with children, and typically, children with minds that couldn’t grasp his meaning and tongues muted by more limited vocabularies.

Ryan’s mind worked fast, fueled by a voracious appetite for printed words.

He was reading above his grade level when he started kindergarten.

“It was like a switch,” Richard said. “A switch went off and he could read and that was it. He could read.”

From kindergarten on, he always had a book open, if not in his hand, within arm’s reach.

“He would read everything,” Bernadette said. “He would read anything. You couldn't be any place and he wouldn't read. He would read the toilet tissue roll, you know what I mean. He just loved the language. He spoke early. He loved to play with words. When he was real little he would say things like 'uppy duppy, potty watty,' all the rhyming stuff. He would just do it naturally. Ryan just loved it. He just loved the language.”

The Bergman’s think Ryan’s advanced skills with the English language drove some teachers crazy. One counselor warned Ryan’s teachers not to engage with him verbally, “because he’ll just chew you up.” Some teachers couldn’t accept that this elementary school student might be smarter than they were.

“There’s always going to be kids who are smarter than you,” Bernadette said. “I don’t care who you are, just suck it up and embrace it, you know, because there’s other things you can teach them. In Ryan’s case, it was organizational skills.”

The lack of organizational skills is what led to Ryan’s second turning point, downhill, when he was 13, in sixth grade. Ryan was accepted into an advanced mathematics program at the University at Buffalo.

It was an odd fit. Ryan, the word guy in an advanced math class at a university. He really wasn’t good with numbers, but his innate ability to reason through puzzles made higher level mathematics, where it becomes more about theory and logic than formulas, easy.

Except for one problem: Ryan didn’t grasp how he arrived at his answers. In mathematics, where part of the problem-solving regime is showing your work, Ryan couldn’t explain how he arrived at his solutions. He got the answers right, he just didn’t know how he got there.

Also, he often didn’t turn in his homework.

"In his mind, 'OK, here's the homework,' ” Richard said. “ 'I did the homework. It's done.' But you have to turn it in. You have to hold onto that piece of paper, you've got to take it with you, you got to turn it in, but in his mind, 'I did it.’ ”

Pok-e-Mon was big at the time and Ryan had a collection of cards. When Bernadette met with the UB teacher about her son’s difficulties in the class, the teacher had a hard time buying that Ryan innately lacked organizational skills.

The teacher noted Ryan’s well organized box of Pok-e-Mon cards. Surely, that was proof, she said, that he was capable of being organized when he was motivated.

“I told her, ‘One, I organized them for him so he would fit in, so that he could use them,' ” Bernadette said, adding, “ ‘but, two, he lost them here. He has no clue where they are.’ ”

Ryan was devastated when he was sent back to a regular math class at Pembroke.

“He just shut down the math side,” Bernadette said. “He was embarrassed. Here was something he could have flourished at, but now he’s back at Pembroke.”

And none of the professionals picked up on Ryan’s growing mental issues.

“The tip off (to the professionals) should have been, verbally, he was very strong, in the 99.8 percentile, but the math part, he lagged behind,” Richard said. “That’s usually a tipoff that something is going on. When you get into the gifted math program, you go, ‘How can that be?’ ” But on standardized testing, he was superior in language and was behind in math.”

Even in areas where he should have excelled socially, he became a pariah.

In the pre-Internet days, computer geeks formed social clubs, called LAN groups (LAN: local area network). They would bring their bulky desktop computers to a group member’s house, string them together with Ethernet cable and a network hub and play computer games.

“He was very good with computers,” Richard recalled. “He would, you know, actually read the manuals. He was able to do things other kids couldn’t.”

For some kids, superior knowledge is a pathway to friendship. I help you and you help me. For Ryan, he could use his advanced computer skills to bully the other kids.

“It got to the point where he (the kid who hosted the group) didn’t want Ryan coming over any more,” Bernadette said. “He didn’t want Ryan over because his other friends didn’t want him over. He would screw up their computers and sitting next to them, he would aggravate them either physically or verbally.”

Like many children with attention difficulties and a tendency toward hyperactivity, Ryan was prescribed drugs, such as Ritalin. Sometimes, Ryan would take his medication as prescribed. Sometimes, he wouldn’t. He would hide his pills around the house and then take several pills at once just to see what it was like.

A psychologist — the same one who warned teachers Ryan could out talk them — told the Bergmans that children like Ryan, superior verbal skills, struggling to fit in socially and academically, who were once at the top of their class, but lost their way as organizational skills become a part of the educational process, typically become depressed and take their own lives.

At age 16, Ryan tried to do just that, using the prescription medication he had available to him.

“He was still under care of this doctor and still going to Pembroke,” Richard said. “The doctor was like, ‘I didn’t see this coming.’ And we thought, ‘You’re the one who warned us and now you say you didn’t see it coming?’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘I thought his ego strength was so large that he would never do it.’ And we were like, ‘His ego strength is there because he’s covering up for the fact that he doesn’t fit in.’ ”

Richard and Bernadette Bergman have all the attributes of ideal parents — steady jobs, a stable home life, community involvement, an active church and social life, and an abiding desire to be parents.

Ryan isn’t the first child Richard and Bernadette tried to adopt. First, there was Jeffrey, a special needs child who has never lived with them, but still has a room in their house and often spends the holidays, some weekends and other special days with the Bergmans.

Jeffrey is now 46 years old and lives in a group home in East Aurora.

“We call him our voluntary son,” Richard said.

Then Richard and Bernadette learned of a single mother who was going to give birth to a baby girl, so they arranged through an attorney to adopt that child upon her birth.

Preparations were made, documents signed and on the day the child was born, Richard and Bernadette were waiting for the child to be brought to them from the hospital when they learned the mother had changed her mind.

The Bergmans were disappointed. The attorney felt horrible about the turn of events. He promised, “when the next child becomes available, you’re at the top of the list.”

It was 1987. A 15-year-old girl in Erie County gave birth to a little boy. He became Ryan Bergman. He came to live with them in their turn-of-the-century home in a little hamlet in the Town of Darien that once was known as Fargo Village, with a train station on the Delaware, Lackawana & Western Railroad line and a little schoolhouse at Fargo and Sumner roads.

At some point in Ryan’s young life, the Bergmans learned through a sister of the birth mother that the young lady had her own struggles with alcohol, as did her father.

Scientists are still learning about the role of dopamine (a biological chemical critical to brain and body functions) in people’s lives, but it is an apparent factor in drug and alcohol abuse and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. These traits could be hereditary.

The Bergmans knew this.

“We warned him, 'Smoking, alcohol, anything you can be come addicted to, you can become addicted to, because there seems to be a correlation,' ” said Bernadette, who has long been involved the Genesee County Mental Health Association.

From a young age, Ryan had a preoccupation with alcohol, not that he was drinking at a young age, but he talked about it, asked questions about it, was curious about it.

There wasn’t much alcohol around the house, though Bernadette liked to have an occasional drink, but Ryan was fixated on the idea of alcohol.

“He was obsessed with talking about it,” Bernadette recalls. “In our mind as lay people, that just seemed, you know, an obsession.”

The response of GCASA (Genesee Council on Alcoholism and Substance Abuse)?

"We don't see any problem here. Kids always talk about alcohol."

Ryan decided he was Irish. And the Irish, of course, have a reputation for boozing it up.

“He was starting to embrace the idea by the time he was a teenager,” Bernadette said. “We have no idea if he has any Irish blood in him or not, but he decided he was going to be Irish.”

Ryan started going to parties with friends. Richard and Bernadette weren’t sure if there was alcohol involved or not, but they suspect there was, then one night he came home plastered.

They think Ryan might have been the one supplying the drinks. He had a job. He had money of his own to make the purchase. He was savvy. He could have been buying beverages and supplying them to his peers.

“It was a way for him to be accepted,” Richard said. “If you’re an outsider, this is an in. ‘I can get you alcohol.’ ”

Despite his struggles, Ryan did graduate from Pembroke High School, earning his diploma in 2005.

In August, he entered the Army, but washed out of basic training and was home by October.

It was tough for him to keep jobs. The Genesee ACE Employment program helped and Ryan landed one of his longer term jobs at the Kutter Cheese Factory, working there from July 2009 to February 2010.

He floated in and out of jobs and friendships, apparently using drugs and grappling with his mental health issues. He wound up in a program at GCASA and was working at Pioneer Credit when he met a woman who was 10 years older, married, with four children and a husband and a house in Oakfield. Ryan moved in with the woman and her children, along with the teenage friend of one of the woman’s daughters.

To support their drug habits, they got into property crime, along with a man who was recently released from prison and was on parole.

They broke into a fire hall in Orleans County and were caught because Ryan, disorganized, forgetful Ryan Bergman, left his mother’s mobile phone in the building. The night before the Orleans deputies showed up at the Bergman’s house, the group had broken into a gun club in Cowlesville and stole a computer.

Ryan insisted the woman wasn’t involved in his crimes.

“He was very loyal,” Richard said. “He wouldn’t turn her in because she had kids. He went to jail so she wouldn’t have to.”

He was sentenced to several months in the Genesee County Jail for breaking into cars, followed by weekends in the Orleans County Jail.

“Most parents worry about where their kids will be when they turn 21,” Richard said. “Ours was already in jail.”

He also spent nearly a year in the Erie County Jail when he was caught driving the wrong way on a street near the Buffalo Airport while high.

It was during this time, Ryan became friends with a person who already had some experience with bath salts.

When a friend of the family lost a daughter to heroin, Ryan’s response was, “I don’t do heroin,” Richard recalled, “like it was a lesser drug.”

Bath salts, though, were the product of chemistry, and presumably safe because, at least at the time, they were legal.

They could be bought on the Tonawanda Indian Reservation, and soon thereafter at locations in the City of Batavia. But when law enforcement swooped in and cut off the local supply, Ryan turned to mail order.

Bath salts are easy to find and buy online and can even be purchased as “samples,” which makes hits more affordable.

“It was the best of both worlds,” Richard said. “It was an amphetamine and he could get high or whatever he was taking them for, and it was legal. At least that was the selling point in the beginning.”

The Bergmans were trying to get their son help in those late fall and early winter months of 2013. It was a struggle.

Certain synthetic drugs are known to induce paranoia, and Ryan may have tended toward suspicion already. When he was in the grips of synthetic drugs, he could distrust anybody and everybody.

A family friend, an attorney, named David, found him out and about and tried to help him. Ryan asked him, “How many pieces of silver was Jesus sold for?”

David said, “I don’t exactly remember.”

“See, David would know the answer to the question, so you’re not David.”

Eventually, David got Ryan home and told the Bergmans, “This kid needs to go to the hospital.”

They tried.

One time, Ryan was taken to a mental health institution and the social worker called the Bergmans at home.

“She said we can give him a ticket at the bus station, or he can stay in a homeless shelter or we can sign him into the facility for care.”

To Ryan, in-patient treatment was tantamount to jail.

“I was on my way there to read him the riot act and by the time I got there, he had sweet talked her -- he was very charming -- and he had her talked into letting him go to out-patient treatment,” Richard said. “He just had her wrapped around his finger and now I was the bad guy.”

Ryan didn’t think it did him any good to be taken to facilities in Buffalo, but he thought he might get help at the hospital in Warsaw, so when he would agree to be checked in someplace, he would agree to Warsaw.

But agreeing and actually getting there were two different matters.

Bernadette learned once the decision was made, she had to get the car started, the windows up and ensure the child safety locks were on. Otherwise, once he got into the car, if he did, he might try to escape at some point.

“We’d maybe go around and around for an hour before he would get in the car,” Bernadette said. “Twice, once we got to Warsaw, after we got there, he just ran off. Once a deputy found him at Tim Horton’s (Cafe).”

In December 2013, Richard Bergman realized there hadn’t been mail delivered to his house in a few days.

“I’d come home and Ryan wouldn’t be there, and I’d ask him where he was when I came home, and he said he went out for a walk to blow off steam,” Richard said. “Well, Thursday, there was no mail. Friday, no mail. Saturday, no mail. Then a notice comes and said, ‘OK, we’re restarting the mail you had suspended for three days.’ I asked him, ‘Did you suspend the mail?’ He said he didn’t know what happened, ‘but your name is on it.' ”

Richard confronted Ryan about getting drugs through the mail, but Ryan denied it.

The Bergmans now know that Ryan was getting samples of Alpha PVP from China delivered to their mail address. The evidence: an envelop with the synthetic drug and a packing slip arrived in the mail a couple of days after he died.

In December 2013, Alpha PVP was little known in the drug or law enforcement community, but over the past year news about its deadly effects have burst into the news under its most common street name, "Flakka," and those reports are what prompted the Bergmans to contact a local reporter more than a year after his initial interview request.

They’re very concerned about how easy it is for young people to buy these dangerous drugs. They don’t know the answer, but they think people should be more aware of what’s going on.

“If you can’t control in anyway how this stuff is getting into the country, you’re never going to be able to address it,” Richard said. “If it’s that easy to obtain, it’s like, how can you blunt that?”

Bernadette remembers sitting in court one time waiting for Ryan’s case to be called and another drug addict accused of a crime stood with his lawyer before the judge.

“The judge says to the lawyer, ‘How many times does he need to go to rehab?’ and I want to say, ‘As many times as it takes,’ and that’s basically what the lawyer said. We need lawyers to understand. We need judges who understand. That would all work easier if the insurance and medical professions had a greater interest in getting a handle on this. My fear is that maybe (bath salts) isn’t as big as heroin, but it’s just so easy to get. You can order it from the comfort of your own home and it comes in the mail and maybe kids see that as no big deal.”

The Sunday before Christmas 2013, Ryan didn’t want to be checked into Warsaw, so he was taken to Strong Memorial Hospital instead. His father brought him home Monday. He swore he didn’t have any drugs in his room.

“His room was a pig sty,” Bernadette said. “If he had any drugs in there, you could look for them and it would take you a week, so he swore, ‘Mom, there are no drugs here,’ well, obviously, that was a lie. He must have taken all he had.”

On Christmas Eve day, Bernadette knew something was wrong with her son.

“Clearly, he was not well,” she said. “I told him, you have two choices. I can take you to the hospital or I can call an ambulance. We got his bags packed and we’re ready to go and he says, ‘Mom, there’s a third choice. I can do outpatient.’ ‘Yes, but we need to get you stable first.’ Just like that, he takes off. He’s in this room. He’s in that room. He gets the poker (from the fire place) and runs into the bathroom and locks the door. I feel the gush of cold air and I know he’s opened the window.”

Bernadette doesn’t remember if she saw him running into the woods or if she just saw his footprints.

“In my head, I keep thinking I saw him running, but I don’t think so,” she said.

It was 10 degrees that day and Ryan was wearing nothing more than jeans, a T-shirt and sneakers.

She called emergency dispatch. She called her husband. He started home. At this point, she wasn’t scared.

“We’ve been through this before,” she said. “We’ve been through the paranoia before. We’ve called the cops before, and usually he heads down the old railroad bed in that same direction and he comes back, so it’s not like you’re thinking, ‘This is the end.’ You’re thinking, ‘We’re going through this again,’ but this time, he just kept right on going and went through the creek and got a way down the other side.”

The State Police arrived. Sheriff’s deputies arrived. Volunteers from the Darien and Alexander fire departments were deployed in a search of the area. After dark, the search was called off for the night.

It resumed the next morning, Christmas Day.

A volunteer from Alden -- a friend of the family, in fact -- found Ryan’s body.

Another friend, a fellow church member, Chief Deputy Gordon Dibble, Sheriff’s Office, delivered the news to Richard and Bernadette.

But they already knew.

“We don’t believe it was a suicide,” Richard said. “He did all of these risky behaviors that were kind of like, ‘If I die, I die. If I live, I live.’ He cracked up his car twice. It was almost like a sense of pride. After (the neighbor friend) died of an overdose, he told a social worker, ‘How come (the friend) can do it and I can’t?’ He would take these risky behaviors, knowing full well he could die, but probably not intentionally.”

Previously on The Batavian: