Imagine a country with only one kind of cheese. If you can, you're thinking of Russia in the aftermath of the fall of communism.

That was the situation Tony Kutter found on his first trip in 1995 to the former Soviet Union as part of a trade exchange program to help aspiring Russian entrepreneurs learn how to start cheesemaking businesses.

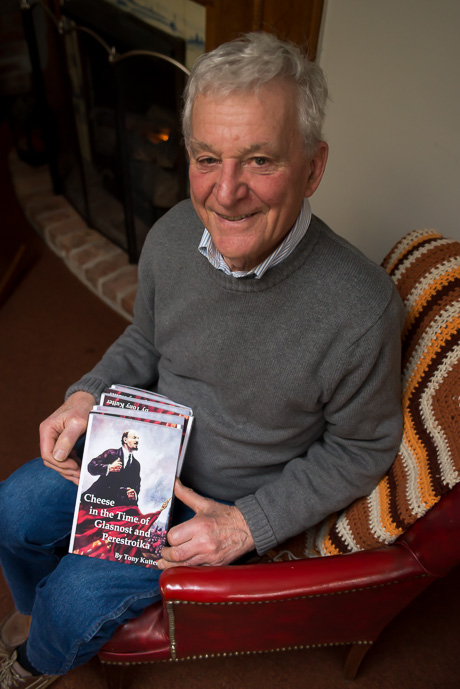

Who better to teach how to make and market more than one kind of cheese than the 81-year-old Corfu resident who is a former owner of Kutter's Cheese, a cheesemaker with a reputation for developing dozens of varieties of cheese.

That's what leaders of the exchange program thought after Kutter volunteered for the assignment and his resume landed on their desks.

It was one of Kutter's suppliers who suggested he apply for the volunteer position.

"He said, 'just send in your resume,' so I did," Kutter said. "I did and as soon as I did they responded right away. 'Oh, this is the one we're looking for.' "

Working through Agricultural Cooperative Development International, Overseas Cooperation Assistance and Citizens Network for Foreign Affairs, all three nonprofit, private organizations based in Washington, D.C., Kutter made 31 trips to Russia over a 12-year span.

Batavia's own Barber Conabel, then president of the World Bank, was among the first to suggest Kutter write a book about his experiences during those many trips.

"He said, 'you've got to write a book,' " Kutter said. "He said, 'I don't know anyone who has been there 31 times and all over Russia.' "

The book is published now and it's called "Cheese in the Time of Glasnost and Perestroika."

Kutter tells the tales, recalls the tribulations and revisits the sometimes sad family histories of the people he met while helping to build cheese plants, instructing cheesemakers on marketing, and sharing with them the recipes for any variety of cheese from munster to gouda to cheese curds.

"I got over there and said, 'geez, you make one kind of cheese and it ain't very damn good,' " Kutter said. "So I took about 20 varieties over from our cheese factory and told them, 'tell me what you want to make and I'll show you how to do it.' "

The organizations sponsoring these missions -- and there were many -- wanted to help Russia transition from a command economy to a market economy and help open up the country to U.S. goods and services. American companies helped sponsor the programs in the hopes of developing a new market.

Goals that haven't exactly been met.

His first mission was to help start a cheese factory in St. Petersburg. This mission was also Kutter's first introduction to Russian bureaucracy and the national penchant to operate on bribery.

Organizations sponsoring Kutter's trips purchased supplies for the new factory and Kutter arrived at the border with the equipment.

A customs official wanted to know, "What the heck is this stuff?"

It's for making cheese, Kutter told him.

The official went through the boxes and proclaimed, "This isn't humanitarian aid. You falsified the papers."

The fine was $75,000.

Kutter returned to the U.S. without the new factory in place, but when he returned a few months later, the factory was ready to start making cheese. All of the new equipment was installed and ready to go.

He wanted to know how it happened.

"Let's not get into that," he was told. "That's not for you to know."

Kutter added, "everything in Russia is predicated on a bribe. It's still that way."

Sadly, the St. Petersburg factory went bankrupt after two years, but others Kutter helped start are still operational.

In his travels, Kutter was often invited into the homes of his Russian hosts and he often quizzed the older Russians about life under the former Soviet regime.

When Stalin died, Kutter was serving in the Army in Korea and he remembers reading in "Stars and Stripes" about people weeping in the streets, so he asked one old Russian gentleman, "did you cry when Stalin died?"

The man said, no. He wasn't really all that saddened by the brutal dictator's death.

The man told Kutter, "I put spit in my eyes so it looked like I was crying."

Kutter had dinner with a woman whose husband was taken to Siberia during Khrushchev's rule.

The couple had eight children. The man's crime? He took a bag of grain so he could feed his family.

The mother wrote her husband every day, but never got a reply. They assumed the letters were getting to him, but that he wasn't allowed to respond.

In 1975, after Brezhnev became chairman, she received a letter informing her that her husband "had been killed unnecessarily." The package contained all the letters she had ever sent him.

"I can tell dozens of stories like that," Kutter said.

In the town of Perm, Kutter helped establish a cheese factory and taught the owners how to make a great variety of cheeses, all of which most Russians had never even tried.

He told his hosts that with these great cheeses ready to sell, they needed a way to market them. Thinking of the booming tourist business Kutter's has always done in Pembroke, Kutter suggested they set up a sample table at City Hall.

As a condition of the permit, Kutter had to speak Russian. Fortunately, he had hired for the plant in Pembroke a woman who was a Russian translator, and she had been tutoring him on his Russian.

"I can speak enough Russian," he told them, "to say, 'I'm from America and I'm working at this cheese plant right here in your city and we developed these new variety of cheese and so perhaps you can try some and tell me what you think.' "

The people came out of the woodwork, Kutter said.

"One woman said to me, 'why are you giving all this stuff away?' " Kutter said.

He told her, "We want to introduce it to you."

She replied, "In Russia, if somebody is giving something away, it usually means it isn't any good."

The Russians liked the free cheese, but that didn't mean they were buying cheese at first.

"I asked one woman, 'would you buy this cheese?' and she asked me what we were selling it for, and I told her, and she said, 'you know, I'd really like to but, no, I wouldn't buy it.' She said, 'I don't have a lot of money, so I would save my money and buy a dress because when I go out in public they can see what I wear, but they can't see what I ate.' "

Asked if he felt he had any lasting impact on Russia, or left a legacy, Kutter demurs.

"I'm just a little old cheese maker," he said.

A little later he came back to the question and recalled the time a sales rep came into the Kutter's factory and asked him if he had heard about the cheese curds recall in Russia.

"I thought," Kutter said, "there never was any cheese curds in Russia until I went there, so I must have had some effect."

"Cheese in the Time of Glasnost and Perestroika," by Tony Kutter, is normally on sale at the Holland Land Office Museum, but they just sold out. More copies are expected soon.