There are an estimated 53 vacant and abandoned homes in the City of Batavia, which creates a drain on city resources, brings down property values for neighbors and are black holes in local economic growth.

It's a problem.

How we go about solving that problem was the subject of a 45-minute talk Monday evening by City Manager Jason Molino.

Forty-five minutes. It's that complicated of a problem.

The city can't legally seize the properties, except for the nine or so that are falling behind in property taxes, and with banks that hold mortgages leaving the properties in legal limbo, there's no way for the city to enforce code violations.

Fixing the problem will take a mixture of tactics: research to locate responsible title holders; trying to locate mortgage holders and convince them to move the title one way or another; convincing Albany legislators to change state law regarding abandoned properties; and creating programs locally to make upgrading abandoned homes more economically feasible.

It's relatively easy to identify which homes in the city have been abandoned. They've stopped using city water.

The 53 homes believed to be abandoned have been vacant an average of three and a half years.

On average, they've generated five visits each year while vacant from code enforcement officers, and one police patrol response per year.

The code enforcement efforts cost taxpayers about $8,000 per year.

Often, the code enforcement citations result in no action because the previous owner who occupied the property can't be located. And though a bank or mortgage holder is continuing to pay taxes on the property, the bank hasn't taken title so it can't be held legally accountable for code violations.

Molino said there's no one answer, and no firm reason is really known, as to why banks don't take title on abandoned properties.

It could be that a large institution is dealing with so many mortgages, nobody is even aware a particular property is on its loan rolls or is abandoned. It could be the company is dealing with so many abandoned properties, some fall through the cracks. It could be that a bank is so bogged down by bureaucracy that it takes years to deal with the paperwork of an abandoned property. It could be the bank has no financial incentive, and some disincentives, to deal with the property.

"We really have to dig into that issue," Molino said. "That's one of the things we really need to look into in the coming months to really understand who are all the lending institutions and why are they not moving on title. ... We really need to get a good understanding of that, because everything hinges on moving title for these properties."

Once a property is back on the market -- either the bank puts it up for sale or auction or the city somehow obtains title -- it becomes subject to the market forces that determine value and the value of restoration.

Molino spent some time explaining supply and demand as it relates to the local housing market.

Since 1960, Batavia has lost 2,700 residents. At the same time, there has been a slight increase in housing stock. During the same time period, people have become more mobile, thinking nothing of driving 20 or 30 minutes to work or an hour and a half to outlet stores. As time as passed, Batavia's housing stock has also aged.

All of this affects the value of properties, the interest of people in living in a place like Batavia, and the affordability of remodeling and restoration.

While there are economic growth activities in and around the city that could lead to more jobs, a population boom isn't necessarily a given.

"Obviously, we'd love to have another 2,000 or 3,000 people come back in the city and increase the demand for housing stock," Molino said. "Realtors would love it. People would be demanding houses and prices would go up. Truth is, that's probably not practical."

Even if economic growth doesn't bring a few thousand more people to Batavia, economic growth is still vital to increasing the value of homes locally.

"If that median income number doesn't go up, then you're limiting your ability to do things, and we can't do a lot of what we want to do or achieve what we want to achieve," Molino said.

What we need, he says, is enough growth to fill the housing stock we have, and then make it economically viable for owner-occupants or speculators to buy and invest in those properties.

Molino used the example of a house currently valued at $50,000. With upgrades, its value might rise to $75,000, but a modernization and restoration project might cost $45,000. That means the owner would need to sink $95,000 into a property that wouldn't be worth more than $75,000 when ready for occupancy.

That's where "gap financing" tools come into play. There are various government programs available. A single program the city could create -- laws would need to be changed by Albany to make it possible -- would allow for abated taxes on the increase in assessed value.

If the assessment goes up by $25,000, the city would tax only on the original $50,000 for the first eight years after restoration, foregoing tax revenue on that $25,000.

That makes economic sense for the city, Molino said, when you consider that's only $230 annually on a property that may currently be costing the city more than $1,000 annually on code enforcement, law enforcement, and lost fees for a property that is abandoned and vacant. Moreover, if a family lived in that home, it would generate from $10,000 to $20,000 in local buying power.

The state needs to pass legislation that would allow Batavia and other cities to create such a program.

Changesare also needed in the laws giving cities more power to deal with banks who let abandoned homes sit fallow, so to speak.

Some of these homes may not be worth saving, Molino acknowledged. While the city may not want to seek demolition of all abandoned homes, some may need to go. That will be a policy decision for the city to make as it learns more about the abandoned housing stock locally.

In the bigger picture, home values are also affected by things related to quality of life, and those, too, are issues the city is taking steps to address or needs to address as part of strategic planning, Molino said.

"When somebody wants to invest on a street," Molino said, "are they going to want to invest on a street on a street that has potholes? Are they going to want to invest on a street that has sidewalks that are turned up? Are they going to want to invest on a street where the neighbors don't talk with each other? Are they going to want to invest on a street where they've got to pay another $1,500 in flood insurance? Who wants to invest there? They don't."

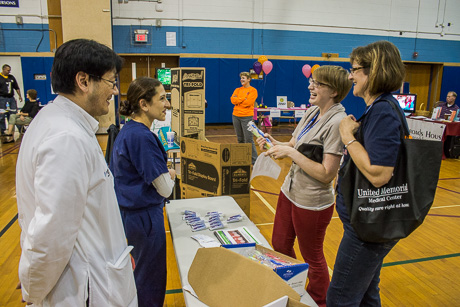

Among Molino's recommendations is creating a home expo, which would bring together representatives of all the various private, government and nonprofit agencies that offer assistance to owners of distressed properties. There's several programs available, but few people know what they all are. Giving residents that kind of information, Molino said, might spur activity that would lead to better housing stock.

Molino's presentation was video-recorded by Alecia Kaus and will be posted to the city's Web site at a later date.