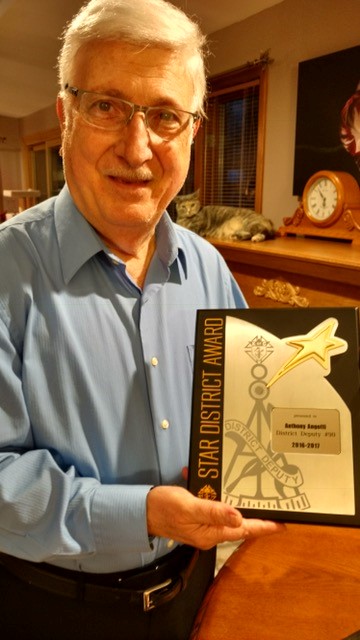

Beers of the World owner Anthony Angotti honored by Knights of Columbus

Submitted photo and press release:

Anthony Angotti, president and owner of Beers of the World in Batavia (a business of Angotti Beverage Corp.) was honored Dec. 2 with the Star District Award by the Knights of Columbus.

Angotti is the only member in New York State to receive this recognition and one of only 18 members worldwide to achieve this designation.

The Star District Award goes to district deputies attaining 100 percent or more of their district’s membership and insurance quotas, and, in addition, at least one of their active councils must attain one of the levels of Star Council.

Anthony Angotti joined the Knights of Columbus Our Lady of the Genesee Council #4812 in April 1993. It was shortly thereafter he became Deputy Grand Knight and then Grand Knight for the same council. During his elected position as Grand Knight, fundraising for those in need were among many of Tony’s responsibilities.

In 1995, he took his 4th degree and then became Navigator at the Bishop Kearney Assembly. He was assigned to guide the 4th degree assembly for two years including fundraising for the Canandaigua VA Hospital. At that time, he also became a Knight of Columbus Color Guard and then went on to become Assistant Commander. The Color Guard’s presence is mainly known at the Greater Rochester International Airport during the arrivals of the Honor Flights. They also perform the Memorial Day and Veterans Day Missing Man Ceremony in Canandaigua.

Tony was elected to the position of Trustee, and then shortly thereafter was appointed the position of District Deputy which he has held since 2014. He oversees five councils within Monroe County including, Our Lady of the Genesee Council #4812 in Henrietta, St. Louis Council #15833 in Pittsford, Ascension Council at St. James #15638 in Irondequoit, St. Stanislaus Council #9326 in the City of Rochester, and St. John of Rochester Council #15917 in Fairport.

His duties include ensuring that all of the Councils have the proper paperwork for the Knights of Columbus State Office, fundraising for the VA hospitals and collecting money and goods for Coats for Kids. Tony also is a member of a group of Knights that purchases or refurbishes chalices to be given as gifts to newly ordained priests.

“After immigrating to the United States 62 years ago, we left our native land with nothing but what we could carry by hand on the boat and no money in our pockets," Angotti said. "I will never forget those that helped us when we arrived and because of that I will forever be grateful. I have a great appreciation for this land and the Veterans that have fought for our freedom.

"It has been such a pleasure being a part of an organization as the Knights of Columbus. My membership has afforded me the opportunity to repay my appreciation by helping those in need especially the veterans of the United States."

About the Knights of Columbus

With more than 1.8 million members, is the world’s largest lay Catholic fraternal service organization. It provides members and their families with volunteer opportunities in service to the Catholic Church, its’ pastors and their community. The guiding principles of the order are: Charity; Unity; Fraternity; and, Patriotism.