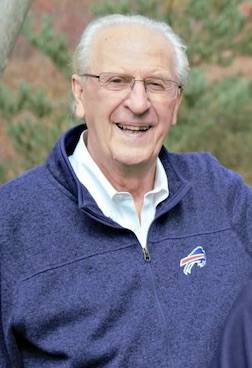

Batavia businessman shares humble beginnings, dedication to local roots

Anyone who has met Vito Gautieri may find it hard to believe that the distinguished Batavia businessman once chased a union rep off a job with a piece of timber, but he swears it’s true.

That was during his first big job — a commercial page-turner in the record books for VJ Gautieri Constructors to build Elba Fire Hall and municipal offices.

“I was in the trenches with the boys pouring concrete, and he tried to get my boys to join the union,” Gautieri said during an interview with The Batavian. “I shooed him off-site with a two-by-four. He left. He was trying all the time. And then there was a masons union guy, his name was Jesse James. He came to the job and asked, ‘Can I buy you a beer when you’re done working?’ I said of course. He told me ‘I’m going to let you finish this job, I’m not going to picket or anything. You’re young and very ambitious. I think you’re going to go places.’”

And he was right. Since Gautieri’s modest beginnings in 1954—working out of an office over his family’s garage on Liberty Street—he has continued to gain the trust of clients in his home territory of Genesee County with projects including City View Residences in downtown Batavia and to the west and east, just completing a $10 million, 188-unit apartment complex in Baldwinsville outside of Syracuse.

See Also: Paolo Busti Cultural Foundation names 2024 scholarship winners for June 4 event

Of course, the way Gautieri tells it, there were a few different twists and turns his life could have taken had it not been for someone sort of guiding his path. Back when he was in the U.S. Army, freshly graduated from engineering school at Fort Belvoir, his paperwork had him going straight to the Korean War. When his mother found out, she raised a little fuss and informed the head honchos that he couldn’t go to war because she had already lost a boy, Vito’s brother Mike, to World War II.

It was determined that Vito couldn’t be sent to a battle zone, so he was stationed in Frankfort, Germany, for two years with the 142nd Signal Company. He wound up as a driver for Col. Hewitt, who took him to various maneuvers. Gautieri was discharged in 1954 and headed home.

Gautieri was preparing to attend college while contemplating a career with the FBI, and you either had to be a lawyer, which took six years, or an accountant, which took four, he said, so “I picked that.” But fate intervened, and Uncle Dominic brought him along to a job building a house for Lou DelPlato.

Gautieri worked with two or three carpenters from the Viele Company there, and “I loved it,” he said, admitting to being instantly attracted to the contracting work. He switched gears immediately.

“And then I came home and told my mother, she had a fit,” he said. “I said I was gonna go into construction, and that’s what I did.”

Before any ink was dry on the Elba deal, there were some council members not so certain that Gautieri had the chops for the job — he was young and inexperienced. Although he was the low bidder for the job, there was the next bidder up working hard to persuade the members to reconsider giving it to this Batavia guy.

The Elba mayor at the time, Anthony Garnish, went to Gautieri’s family home, and his mother brought him up to the garage office to show her son’s professionalism and how he treated the business. Perhaps it was fortunate that Gautieri wasn’t home at the time.

“She said ‘he knows what he’s doing,’ Gautieri said. “She took the mayor up the ladder to the second floor of our garage, that’s where I had my office and did all my estimating and stuff like that. So she took him up there, and she must have been very convincing because Mayor Garnish went back to the board … and he convinced them to give me a job. And that was my first commercial construction job.”

The mayor went back to those board members and confronted some of them about their own meager beginnings, reminding them that “didn’t you start out” with little experience? He got the job for what he recalled was for six figures, which was quite a nice contract back then. He ended up also getting the fire station demo while he was at it.

His later encounters with union reps were another hurdle he eventually realized he wouldn’t win. “You had to be union,” he said, even with another relentless mason rep named Jesse James. They ended up becoming friends, and Gautieri’s company remained unionized until the late 1980s, he said.

“Now we’re an open shop company, we could go union or open shop,” he said.

VJ Gautieri Constructors was part of Urban Renewal, like it or not, because even though a hapless part of Batavia’s history that phase of knock-down America was a lucrative step for local contractors. Gautieri got jobs for Salway, a few banks, Alexander’s clothing store — “we knocked down half of the buildings in Batavia” — and built other projects along the way.

The former Montgomery Ward, site of the current Save-A-Lot and City View Residences, was originally on a 20-year lease, and got out of that in eight years, leaving the building to just sit there. So Gautieri traveled back and forth from Batavia to Pittsburgh and Chicago putting together a deal, and he and other developers purchased the building. Since then, there have been four supermarkets that ended up bailing on Gautieri as landlord, and Save-A-Lot has remained a constant for the last several years.

Gautieri’s vision to renovate the upper floor for apartments came to fruition a year ago. Ten upscale units accessible by an elevator are fully rented and have a waiting list. Other surrounding office space is also occupied by nonprofits and businesses.

He remembers one of the more difficult land acquisitions, around 1980, when a City Council with members including Florence Gioia and Benny Potrzebowski were not in favor of him purchasing the land at Washington Avenue and State Street. It was a five-year tussle that ended when Potrzebowski came back to ask Gautieri to pursue the project.

“He kneels down in front of my desk and says, Vito, I got the votes, come on,” Gautieri said. “So we went here and everything was fine, we got the plans approved. This one guy who was against the project didn’t like the way we laid out the site. I said sir, are you an architect? He says no. I said, ‘I paid $150,000 in architect’s fees, and they’ve located the building the best way for the building. He was the one who voted no, but then I got seven out of nine votes. Then we started the project after five years.”

At the time, Ronald Reagan was an incoming president and was said to be against affordable housing, so the timing was fortuitous for Gautieri to establish his HUD-subsidized senior housing Washington Towers complex. He had a bulldozer quickly move onto the property “and push some dirt around, and we took some pictures, and we started building” just in case there were government changes coming.

Beyond the financial assistance it would give to local senior citizens, the materials used were of prestressed concrete, which “made me feel happy,” he said because if there was ever a fire, it would be a rugged warrior against flames to protect those residents. In fact, there have been a couple of fires there, but they’ve been isolated to a room without spreading, he said.

“When we were getting approval of the plans from Buffalo, they wanted me to do it like 400 Towers, just plain concrete on the outside. I said ‘no way.’ So I finally convinced them that it would be better in the long run for brick, and they approved it.”

They began the project in 1979, completed it in 1980 and filled the 130 units in about four or five months. Tenants pay 25% of their income with the government subsidizing the remainder.

“Affordable housing. I think we still need some more of that,” he said.

He tried to calculate quickly how many projects the company had completed in the city alone, surpassing more than a dozen.

“We have done at least 10 to 15 buildings in Batavia. We remodeled the county building, we had to scaffold it, and we did new roofs, windows, remodeled it,” he said. “We did not do the mall, when they gave the presentation, we took on Kings Plaza, we built and rented it.”

Not every transaction as smooth sailing, especially when it came to doing business with New York State, he said. Late or nonpayments have meant taking the state to court. By contrast, he eagerly worked with “Mr. Carr,” of C.L. Carr’s department store fame, who was as meticulous as he was dependable. There was an electrical engineer on the job with Gautieri’s men, and Carr’s brother was an architect in New York City. The contract was signed on a Sunday as a “cost-plus job,” which was low risk for the contractor, Gautieri said.

“You get better workmanship,” he said. “He was so meticulous, he wanted a second floor all moved back an inch and a half. My guy Charlie came and told me, and I said, do what he says, you do what the owner wants. He was a wonderful man, Mr. Carr. I’d give him the bill today, and he’d give me the check tomorrow. You don’t get that today. Things change, and change is good.”

Gautieri put in a bid for the Carr’s Reborn project but was not the lowest bidder and didn’t get the job. He does hope that “the Carr’s building is very successful,” he said.

Early on, the Gautieri company had its own workers, and time and experience have taught him that “when we see a company that can do a job safer and quicker, we sublet it out,” he said. For example, that job in Baldwinsville had subcontractors for carpentry, masonry, roofing, parking lots and blacktop.

Gautieri founded the first of many Gautieri companies in 1954. General construction was the organization's primary focus for the first decade. In the early 1960s, Gautieri diversified the organization and became involved with commercial real estate development while continuing the traditional contracting portion of the business.

Today the organization offers general contracting, construction management, design/build, property management and real estate brokerage services throughout the Western New York area.

The organization's day-to-day management is handled by a staff that includes his two sons, Victor and Vito Jr., and daughter Valerie. Preparing to celebrate his 93rd birthday in July, Vito participates in regular business meetings but doesn’t go to job sites anymore.

Honored recently as the longest-serving member of the Alexander Volunteer Fire Department (he joined in 1960), Gautieri is also one of the remaining founders of the Paolo Busti Cultural Foundation, which honors the Italian heritage of many locals. There is a Vito J. Gautieri scholarship given out in his honor during the annual scholarship awards dinner, which is on June 4.

While he appreciates the women on the board who contribute and do good work, Gautieri would like to see more men serving on the board as well.

“I’m not happy with that, and I’m going to do something to help move that along,” he said.

Vito has been married to Marjorie (Marge) since 1979. His previous wife, Connie, died in 1977. He has two stepsons from Connie's previous marriage, Anthony Pullinzi Jr. and Michael Pullinzi. The Gautieri children are Victor (Julie) Gautieri, who has assumed the role of president at the company, Valerie (Bobby) Tidwell, Vinessa (Merle) Schreckengost and Vito Gautieri, Jr.