Police officers are often in a position to first pick up on the signs of domestic abuse, and they sometimes deal with people in the most difficult times of their lives.

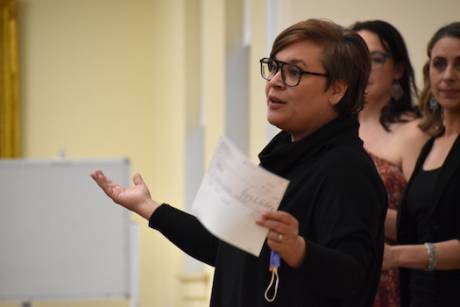

So after a talk at Genesee Community College by author Janine Latus, who suffered a string of domestic abuse traumas in her life, The Batavian spoke to local law enforcement officers about the role of cops in breaking the cycle of abuse.

It takes empathy, awareness, and the knowledge of resources available in the community for police officers to play a role in stopping domestic violence, said Shawn Heubusch, chief of the Batavia Police Department, and Brian Frieday, chief deputy for road patrol at the Genesee County Sheriff's Office.

Heubusch said officers need to bring empathy to every call they answer.

"You have to remember that it could be somebody's worst day," Heubusch said. "Whether it's the second time you've seen them or the very first time that you've seen them, just be understanding of what people are going through. Not everybody deals with things the same way that we do."

Frieday said that one pitfall of the job in dealing with so much trauma is that an officer can become dissociated from the feelings of a crime victim, whether it's a domestic situation or a petit larceny or an accident.

"It's called an accident, but it's really a crash, and that might be the biggest thing in the world to that person on that particular day," Frieday said. "And it might last longer, so we try relaying to younger officers that (this incident) could have lasting effects. It might be the only thing in their life that happened or it might be a lot deeper than what we perceive."

Heubusch and Frieday were at GCC for a Crime Victims' Rights Week seminar, where Latus was the keynote speaker. Latus wrote

If I'm Missing or Dead: A Sister's Story of Love, Murder and Liberation, which is as much about her murder of the author's sister by a boyfriend as it is about her own life. Latus was the victim of multiple abusive men.

Focus on victims

The first takeaway Heubusch and Frieday had after the talk was always to keep the victim in mind, which brought to mind immediately the struggles police officers are facing because of bail reform.

"The victims are underrepresented at this point," Heubusch said.

Frieday agreed.

"The focus should be on the victims," Frieday said. "They're the ones who are suffering the consequences, suffering the losses, based on whatever crime or action the defendant or suspect did to them, whether it's financial or physical. The focus has gotten turned around to the wrong side."

Under the current bail laws, if there is a human victim of a crime, an officer can bring the suspect in front of a judge for arraignment, and a judge can issue an order of protection, but except for a very few circumstances, the judge cannot order the defendant held in jail.

"We've had instances where we've seen that person leave court, walk to the house, violate the order of protection, sometimes, through an assault," Heubusch said.

Signs of abuse

Latus talked about noticing the subtle signs of abuse. She used the example of a talk she gave where a young man asked a question, and she answered it. After the talk, the young man came up to her and told her why he was wearing long sleeves. When his girlfriend fought with him, she would drag her fingernails down his arms and cut him. Sometimes he wore hoodies to hide the wounds. It's little things like that, Latus said, people should watch for in friends and family members that might alert them to possible abuse.

Police officers aren't social workers, but they often come into family situations that could alert them, if not explicitly, perhaps implicitly, to abuse. That's why it's important for police officers to know about the resources available in the community to assist both victims and perpetrators, Heubusch and Frieday said.

In attendance on Monday were staff members from Genesee Justice, the Child Advocacy Center, as well as professionals who work with sexual assault victims, domestic violence victims, and substance abuse counselors.

"There are avenues that are available in the community that we have access to at least get them to, or at least try to, like one of the early presenters said, the worst they can do is just say no, but we're trying to lead them down paths that could get them to help," Frieday said.

In the schools

Heubusch said one of the early warning systems now available are School Resource Officers. They are in a position to spot problems before crimes are reported.

"Sometimes they're seeing things, or the school is seeing things that we're not necessarily seeing or hasn't risen to the level of an enforcement action or police officers being called to a home, but they're seeing the kids come into the schools day after day with a multitude of issues," Heubusch said. "Again, (they can use those resources) as a clearinghouse to get them to the resources that Chief Deputy Frieday mentioned. There are just so many available to them, and we just have to get them there."

Frieday also said SROs now play an important role in identifying potential domestic abuse.

"They see the kids on a day-to-day basis," Frieday said. "They see trends in their behavior, or, you know, differences in absences, truancy, and everything like that, that they can have those talks. A lot of times, it's in conjunction with the school, but they can get out ahead of that sometimes and tell them, 'Hey, you're on a bad path. I've seen this. What can we do to help?'"

Domestic abuse is known to elevate over time, or certainly not end without intervention but officers also must be careful about how they approach a topic that can be sensitive for victims.

"When it comes to victim blaming, we have to be very careful when we try to tell a domestic violence victim that potentially you're going down a bad path and you are going to be hurt if you don't do X, Y or Z," Heubusch said. "We have to be careful because we're not a judge, judging that person. We don't want to feel that person to feel judged. But we want to relay to them that there are services that can help them. We absolutely have a role to play in that, especially when it comes to the suspects, identifying what they're doing, holding them accountable, or doing our best to hold them accountable, and advising them that this is not going to make your life easier."

A history of abuse

For Latus, her bad path started when she was young, working as a babysitter, when she was abused by a part-time teacher. Then while working in a hospital, she got involved with a medical student, a wealthy young man.

She learned one Thanksgiving that his father was abusive and told herself, she needed to be there for him, then, on a ski vacation, she said the wrong thing, and her boyfriend punched her in the face, in the ribs, and kicked her while she was on the ground. Then blamed her for making him do it.

Her sister was her moral support, but Latus didn't want to cost her boyfriend his medical career, so at her sister's suggestion, she contacted another doctor she knew. He came to her house and nursed her broken nose and broken ribs. He was caring and attentive. They fell in love. He was married and eventually left his wife for her.

Her husband was controlling and jealous, and threatening. She told stories of the creepy things he did and how she blamed herself. Eventually, her sister helped her leave him.

Her sister found a man. A cowboy. She worked. He didn't. It turns out he had a criminal record. The sister bought him everything he needed to become a painting contractor. She always portrayed her relationship with her man as happy and loving.

Then she disappeared.

Eventually, authorities found a note taped under her desk, written 10 weeks before she disappeared, that began, "If I'm ever missing or dead," and pointed law enforcement to her abuser, her boyfriend. Her body was found at a construction site wrapped in a painter's tarp, and her boyfriend served 20 years in prison for her murder.

Latus said she wrote the book to encourage people who are abused or know about abuse to speak up.

Avoiding abuse

"If I didn't pretend everything was perfect, my sister would not have had to pretend everything was perfect," Latus said. "I wrote this book to save other angels."

She shared some things abusers do:

- They use coercion to obtain sex.

- They use financial resources to exercise control.

- They use social media to isolate victims (such as sending messages to friends using their partner's account to say things like, "I hate you.").

- They use mobile devices to track partners.

- They use technology to make the other person feel stupid and unworthy.

"None of those things raise a bruise," she said.

During the Q&A at the end, she was asked if the man who first abused her was ever arrested. She said authorities learned he had multiple victims around the time she was abused, but because he never penetrated, by the time the crimes were uncovered, the statute of limitations had run out. She asked a former classmate as a result of that investigation, if there were any other "creepers" in town. The former classmate said, "Yes, your father."

Research has shown that people tend to pick partners who are like former partners. Asked how people can break the cycle of abusive partners that Latus seemed to grow through, she said if you leave an abusive relationship, don't get involved in a new relationship right away.

"I absolutely recommend what I call a dating sabbatical," Latus said. "Take time off. Don't go to the next person to save you from this. Stay by yourself. Go to dinner by yourself. Make friends, go to movies, discover that you're great all by yourself, that you're comfortable and happy. Embrace the view that you are the best company you've ever had. And then the person you're going to be attracted to and appreciate and attract to you is probably going to be healthy, happy and whole, too. If you're insecure, you are going to attract an insecure person who is going to exploit you. If you are solid in yourself, then the person you're going to choose is far more likely to be healthy."

Photos by Howard Owens.